If music has taught us anything in this century, it’s that the world gets smaller as the internet gets faster. But for a fifth of the world’s population, music portals like YouTube, SoundCloud and Spotify are only been accessible to those who can crack the so-called “Great Firewall of China” and sidestep the country’s harsh censorship.

Words by Chal Ravens

It’s not impossible, of course – and so, in recent years, a new generation of Chinese DJs, producers and clubbers has begun to break down barriers and make their mark internationally. After years of importing dance music from the west, China is seeing its own electronic subcultures flourish in cities like Shanghai, Chengdu and Shenzhen, while nightspots like ALL and OIL Club are booking all kinds of European artists, down to the most extreme and experimental. It’s almost a running joke, says Tzusing, one of Shanghai’s most respected electronic artists and a catalyst for the city’s new wave of experimental club music: “Everybody has a China tour now!”

Tzusing is one of three Chinese artists booked for Dekmantel Festival in 2019, along with Yu Su, a Vancouver-based house newcomer whose dreamy, new age-influenced tracks have appeared on PPU and Second Circle, and object blue, a Beijing-born, London-based club provocateur who pairs sleek sound design with rough-edged samples from hip-hop and kung fu movies. With their diverse backgrounds and musical obsessions, these three artists represent only a fragment of the vast plurality of experiences in modern China and its global diaspora; all three operate at a cultural crossroads, having either relocated or spent time abroad.

Tzusing has been setting the pace for Shanghai’s underground evolution for a decade through his audacious DJ sets, his agenda-setting clubnight Stockholm Syndrome, and his own bone-rattling club productions on labels like L.I.E.S. and Cititrax. Born in Malaysia and raised in Singapore and Taiwan, Tzusing spent a few formative years studying in Chicago before settling in his twin bases of Shanghai and Taipei, Taiwan’s capital. In the eight years since he launched Stockholm Syndrome at The Shelter, he’s seen Shanghai’s expat-dominated club scene transformed by an influx of Chinese youth who are the product of a booming middle class. “These kids aren’t looking for what their parents wanted, like luxury items – they want something else. It’s about money getting older,” he notes. And with the change in demographic comes a change in style. “Chinese kids never really had this clubbing culture. People go to bed earlier and go out earlier as well. So people would DJ however they wanted to and play music in a way that was not genre-specific. You might have bangers at 11pm and then at peak-time it would be an ambient track,” he laughs. “The technical proficiency is getting higher now, people are becoming better DJs. But that initial freedom was really important to jumpstart things."

Tzusing’s own irreverent mixing style – blending ghoulish techno, breaks and bass with freaky flips of US rap and Chinese pop – paved the way for the stylistic shift towards “deconstructed club music”, as found on young Shanghai-based labels like SVBKVLT and Genome 6.66 Mbp. “I've always felt very restricted by playing in the European way – proper, “correct” DJing,” he explains. Stockholm Syndrome allowed him to break free from the rules of house and techno, and “the deconstructed club style is a more extreme version of that. It came out of the internet, and it’s made by kids who grew up listening to a lot of different stuff. Genre is meaningless at this point, after MP3s, and I’ve always related to that.”

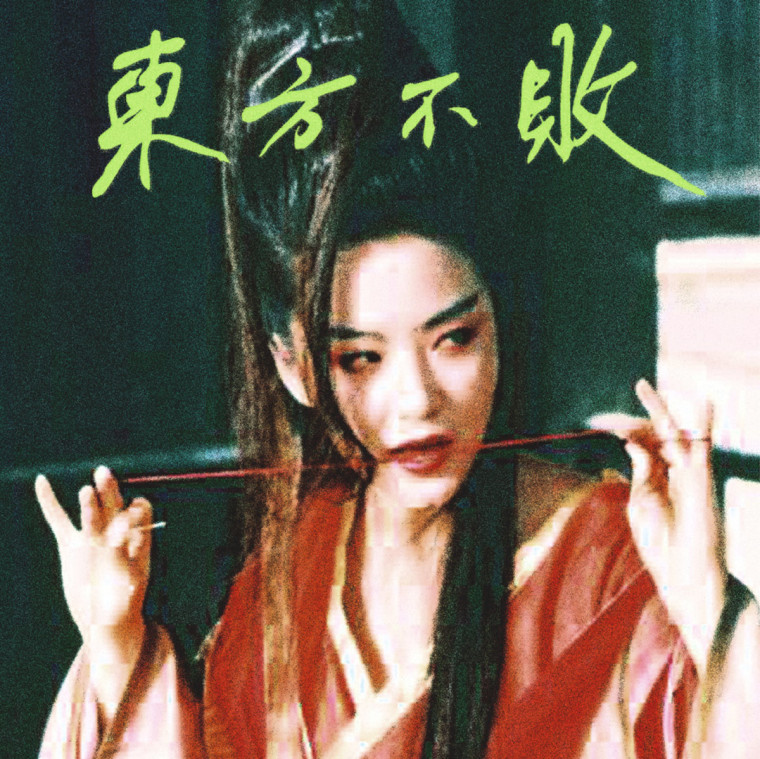

On Tzusing’s 2017 debut album 東方不敗, martial rhythms and industrial textures are punctuated by characteristically Chinese sounds, like tuned percussion and reedy synth tones. Along with the title and cover art – a still from a Hong Kong martial arts movie – listeners are left in no doubt as to where this album was made. “A lot of my friends gave me shit for [the cover] because it's a Chinese woman. For the western market it’s easy to exoticise this thing, right? But I chose that character not thinking about the western market,” he explains. “I wanted to appeal to a younger version of me. I wanted Asian kids to have a record that was referencing things they understood and could relate to. So I try to not think about how this will be perceived in the west – it just seems like a lot of stuff to worry about.”

For Yu Su, making music is an opportunity to investigate a more obscured aspect of Chinese identity – not in the sounds or outward aesthetic of her mellow, meditative records, but in her approach to creativity. Growing up in the small city of Kaifeng – an ancient capital of China that was once “the New York of the world,” she says, but is now a crumbling tourist town – Yu Su learned piano to concert level but had minimal contact with western pop music: “The internet wasn’t that great when I was growing up. Nothing was that accessible.” After moving to Vancouver for university in 2014, she began to convert her musical knowledge to dance music after a disco epiphany at a Floating Points show.

Often recording tracks in one sitting, Yu Su combines elements from jazz, library music and the new age tradition of the Pacific Northwest in an approach inspired by Taoist philosophy, the focus of her studies in East Asian religion. Taoism as a belief system has only a tiny number of committed followers, but its concepts of balance and harmony are ingrained in Chinese culture. Yu Su integrates these principles into her own practice as a sound artist and musician, making lush, meandering deep house inspired by crews like Vancouver’s Mood Hut and DC’s Beautiful Swimmers. “I want to bring this idea of just going with the flow, because things always happen unexpectedly. One day you find an opportunity in front of you that's something you've wanted for so long – it just happens,” she says. She uses the example of the yin yang symbol, which comes from Taoism, to explain how opposing forces must exist at the same time: “Black goes into white, white goes into black – one thing goes into its opposite. There’s no absolute, one or the other.”

Since arriving in Canada, Yu Su has realised that this “go with the flow” attitude is totally at odds with North American culture, which values hard work and constant striving. “I experience a lot of culture shock,” she says. “One big thing I’ve noticed is this difference of collectivism and individualism. I see that within the music and art scene, where people are very outspoken about their own opinions on everything. I’m not saying that is bad – it’s just different from where I come from.” She likes to think that her subtle seeding of Taoist ideas may bring some balance and harmony into people’s lives. “Everyone’s always stressed out about everything,” she says. “I want to remind people that sometimes your own opinion doesn’t matter since you are such a tiny grain of rice in this whole world of moving matters and beings. It’s this Taoist idea that things will happen when they happen. ”

While Tzusing plays with western preconceptions of Chinese culture and Yu Su digs into obscured aspects of the national psyche, Beijing-raised DJ and producer object blue prefers not to make any connection between her visceral, volatile club tracks and her Chinese identity. “I'm the kind of person who gets pissed when people write about my ‘Asian influence’,” she states, pointing out that her biggest influences are “people like Alva Noto and Björk”. “I don’t mind if people notice that I sample a lot of kung fu films, but when they say my music has an Asian influence I feel like they’re just trying to fit me into this cultural trend of ‘cool Asian people’.” On her off-kilter releases for TT and Let’s Go Swimming, she flips Cardi B samples and fragments from arthouse movies into cavernous drum assemblages; there’s a subtle connection between her murky, uneven approach to techno and Tzusing’s outsider club noise, she suggests – a darkness that “might have been influenced by us living in big industrialised cities.”

Born to a Chinese father and a half-Japanese mother, object blue spent her early years in Japan and didn’t even think of herself as Chinese until the family moved to a suburb of Beijing. As a teenager she was “super sheltered”: “I was grounded for four years because I was caught going to a bar instead of a sleepover.” After a few years studying abroad, she returned aged 23 to brush up on her Chinese. “By that time I knew I loved techno. I went to Dada in Beijing – a great night. That’s where I ended up playing last year.” With another outpost in Shanghai, Dada is one of China’s longest-running techno institutions – but operating a successful club in Beijing comes with its own challenges. “There are a lot of creative people and a lot of subcultures in Beijing, but because it’s the capital it’s usually under more government surveillance,” her explains. “Nightlife is more effectively suppressed – there’s more police and stricter licensing.”

Having a Japanese passport has afforded object blue various privileges that her Chinese friends don’t have – freedom from censorship, for a start, and the ability to travel with ease. She thinks that in a restrictive society like China’s, fringe music and subcultures “end up becoming more and more extravagant.” While artists from Japan and Korea are revered as unique and cutting-edge, “China doesn’t have an advantage. It’s still considered quite uncool. Chinese people feel left out, and maybe that's why they go into an extreme aesthetic – like Asian Dope Boys,” she says, referencing Tianzhuo Chen’s transgressive performance art troupe. “They don’t give a fuck anymore. They're pushing back against something.”

While object blue has planted roots in Europe, Yu Su sees herself returning to China to be part of the country’s booming electronic underground. It’s about time the rest of the world knew what was going on behind the Great Firewall. “People have been doing experimental music in China for years and years but no one knows about it. Even just five years ago it was way different,” she says. Tzusing is more than optimistic about China’s next generation of “young, passionate, and kind of romantic” ravers. But, he adds, for him “the ultimate goal is to get to a point where we can just talk about our music, and our identity isn’t that big a part of it."