When water returns to the wetland, you expect it to bring sounds to life—birds in a spring song, shuffling winds, and the slurp and slosh of sludge. Enter: The Swamp, the first instalment of Lentekabinet’s new festival stage that sheds a spotlight on homegrown and international artists of South West Asian and Northern African descent.

Words by Agri Ibrahim

Originally published on May 17th

A couple of summers ago, I heard a sound slither its way onto every dancefloor I found myself on: heady percussion of darbuka drums and its dancefloor-ready patterns. There was something infectious about it—a combination of emotions; sad yet celebratory, over-engineered yet incredibly simple. It was not only infectious, but contagious: it made the most lifeless, wading bodies acquire some sort of rhythmic sensibility. Hips defrosted, people were sent into collective emotional frenzies. It seemed as though no one in the sound’s proximity could safely escape without busting out a move or two.

Today, those same drum patterns are consistently drip-fed onto global dancefloors. DJ Plead’s SUMAC label (eponymous to the crimson red spice popular in SWANA region), for example, delivered a slab of percussive heat with ‘Ruby’ (which sampled Lebanese icon Ruby’s ‘Leih Beydary Keda) and ‘Clap Clap’ (co-produced with Anunaku). Egyptian 3Phaz dispatched some hard-hitting percussions of shaabi and mahraganat, a combination of genres popularised by working-class Egyptians, traditionally played at weddings. And let’s not forget Deena Abdelwahed’s ‘Khonnar’, her critically acclaimed debut album that seamlessly blends dabke folk rhythms and rotating bass patterns.

It’s safe to say that a notable movement of SWANA sounds is expanding across Europe and beyond. The post-pandemic era has ushered in a generation determined to recontextualise popular music from the SWANA region and reimagine what it could sound like. These pioneering artists facilitate potent music exchanges and collaborations with diasporic communities. An auditory alchemy, if you will, takes place. Saz guitar samples from Anatolia get coupled with arpeggiated synths and darbuka percussions—and it’s not a casual tie-up, but a byproduct of a generation on a boundless quest to trace the relics of their heritage together.

The post-pandemic era has ushered in a generation determined to recontextualise popular music from the SWANA region and reimagine what it could sound like.

Despite studies highlighting the SWANA region as one of the fastest-growing music industries globally, individuals and artists are often reduced and shoved into pocket-sized, catchall terms. Simultaneously, this generation is on a mission to rectify errors and dispel myths around the single-minded, monolithic stereotypes often imposed by the West. On that note, let’s unpack the catchall term ‘SWANA’. ‘SWANA’ represents Southwest Asia and North Africa, the decolonial marker challenging Eurocentric labels like ‘Middle Eastern’. Ironically, there is nothing ‘Middle’ nor ‘East’ about it, thus rendering itself useless for geographical accuracy—even by its own metrics, the ubiquitous ‘Middle Eastern’ term is inherently false. Using ‘SWANA’ as a decolonial term instead is a small but considerable step towards agency and creating a more accurate portrayal of the region, and its diverse people(s).

Etran de L’Aïr

Conceived at the very heights of Northern Niger’s mountainous terrains, Etran de L’Aïr is a quartet of charming family members brought together by Aghaly Migi. The band is based in Agadez, a city in Niger whose DNA is anchored in music production, more commonly known as the world of Tuareg music; a ‘desert blues’ created by a nomadic people hailing from all across the Western Saharan region from Morocco to Mali. As of late, it is also popularised by bands such as Mdou Moctar and Bombino.

A unique combination of jazz and blues rock, Etran de L’Aïr’s changes in melodic solo lines and accompaniment parts are as unpredictable as the unending desert of Niger. “We play with chords, accompaniments, and guitar techniques” they explain, “often swapping parts to improve our fluidity and flexibility.”. For the band members it’s the magic of their spontaneity that defines the vibrancy of their music and transfixes their audience. “Our ability to interchange roles is what defines the beauty of Etran de L’Aïr, Agadez, Niger.”

Where most Tuareg artists use the electric guitar to emulate Western rock influences, Etran de L’Aïr uses it to evoke a pan-African style that is unique to the sounds that bleed out of Agadez. Their influences include Northern Malian blues, Hausa bar bands, and Congolese Soukous. And while the sounds of Tuareg have expanded and migrated, diehards consider Agadez to be their birthplace.

There are touching parallels between the underlying (or overt) music politics of both Tuareg and rhythm & blues—the genre originating from New Orleans in the 1940s, minted by the iconic Henry Roeland “Roy” Byrd, also known as “Professor Longhair”, who invented its distinctive beat.

Much like the Black community pioneered rhythm & blues in the United States, the Tuareg community has historically used Tuareg music (desert blues) as a device of upheaval against towering colonial powers; French colonialists in the 1910s, the Malian government in the 1960s, and most recently, in the 1990s, the governments of Niger and Mali. For this community, musical autonomy has been rehearsed as a reclamation device for the many ways in which they can resist foreign draconian powers.

My exchanges with Etran de L’Aïr make clear that it isn’t just about music; it’s about music as a vessel for bringing people together. “Bridging this gap and expanding the sound from the Sahel region towards other parts of the world is extremely important as it creates understanding”, the band ruminates, emphasising how “sharing our music with different parts of the world strengthens the ties and relationships between nations. Preserving these relationships through sharing traditions and culture is essential for creating a favourable climate, facilitating messages of peace, solidarity and support”.

“Sharing our music with different parts of the world strengthens the ties and relationships between nations." - Etran de L’Aïr

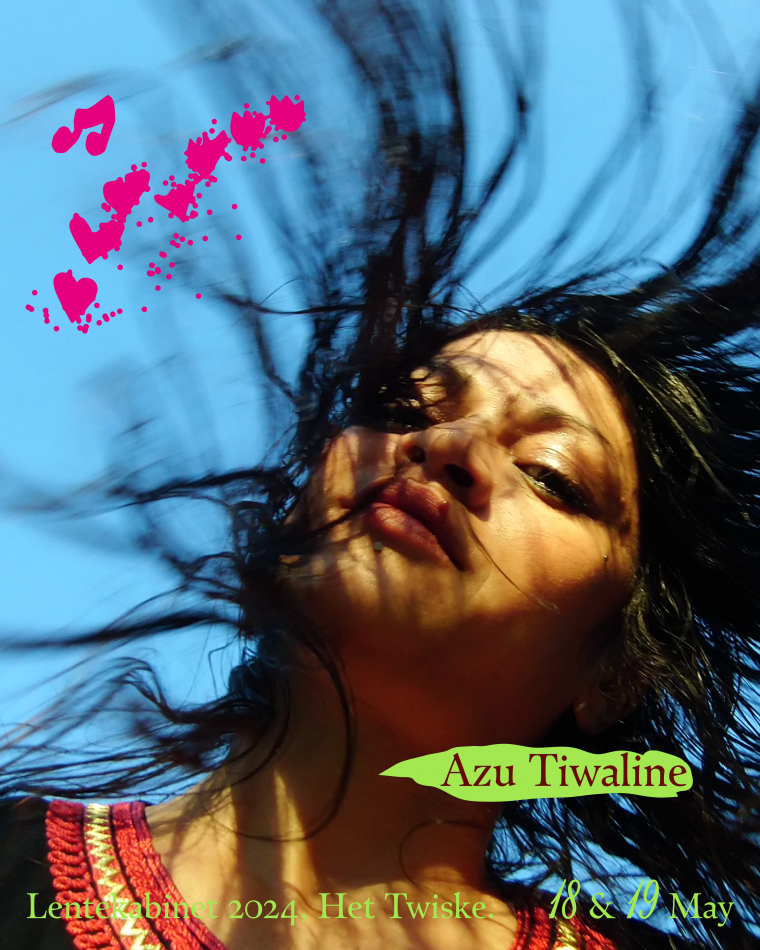

Azu Tiwaline

Hailing from Tunisia and Cambodia via the Ivory Coast, Azu Tiwaline is an artist and producer on a boundless quest to explore her amalgamating heritage. Where others see opposition, Azu sees opportunity; her richly impressionistic, instrumental narrative weaves together ASMR cuts with hauntingly beautiful echoes of field recordings.

Azu’s second album, ‘The Fifth Dream’ (released via Marseille’s I.O.T Records & Bristol’s Livity Sound), is a masterful display of how the artist brings seemingly opposing forces so close together that they become inextricable. “Experimental music pushes my boundaries, exploring unconventional sounds and techniques” she tells us. “In essence, the nature of the music I produce is a fusion of these influences, with a deep hypnotic and trance state intention, to transport listeners to my intimate sonic realms.” Her expansive palate ties together a multiverse, painting a picture so vivid and engaging you find yourself lost in its ritualistic undertones.

“In essence, the nature of the music I produce is a fusion of these influences, with a deep hypnotic and trance state intention, to transport listeners to my intimate sonic realms.” - Azu Tiwaline

Currently operating from–and living in–the El Djerid desert, Azu pulls elements of her Tunisian heritage and sub-Saharan nativity into play with rhythmic dub and the dynamic exuberance of techno. “I really need to live in wild and isolated places as much as I can” she discloses, “especially to be able to focus on my creativity and well-being”. If you listen to the artist’s ‘The Fifth Dream’, you’ll hear chants cascading down a mountain range, and recordings of the deserts lighting up each song. These field recordings, picked up in El Djerid like excerpts, pop up like microcosms in her innovative sound design.

LazerGazer

Minted as “brutal ambient in your headphones” and “bass in the club”, LazerGazer (Hala Namer) is no stranger to the Amsterdam clubbing scene. Whether she spends her time crisscrossing Kanaal40 and Garage Noord––her local residencies––or in a faraway country, this Damascene-Kurd will promise an ounce of sheisty electro and a heaping spoonful of breakbeats. Jaw-swinging, eye-fluttering and grin-inducing; LazerGazer’s recent Boiler Room for Sawt Syria [Sound Syria] rips her diasporic sounds to shreds and lets them be born anew.

When asked about the compelling nature of sounds hailing from South West Asia & Northern Africa, LazerGazer has her own qualms with the term SWANA. “To lump all the sounds from the region under one generic ’sound’ would be quite an oversimplification”, she tells us; “Each country within the region has its own unique musical landscape, influenced by geographical variations”. LazerGazer recognises that by perpetuating these catchall terms, you by definition run the risk of oversimplifying the differences in languages and cultures. “Musically speaking, we can’t keep putting everything in the same box––it’s too reductive”.

“To lump all the sounds from the region under one generic ’sound’ would be quite an oversimplification. Each country within the region has its own unique musical landscape, influenced by geographical variations”. - LazerGazer

LazerGazer’s influences pull together a slew of experimental sounds that are as expansive as the music she plays: including Palestinian artist Maya Al Khaldi’s use of archival sounds, DJ Al Nather and his work behind BLTNM, and Egyptians ABADIR and irsh On a more frequent day-to-day basis, her influences are personal and heartfelt. “What influences me is what’s left from my upbringing and experiences in Syria. A lot of environmental sounds that I picked up growing up that stuck with me forever”, she expands. “The soundscape in Syria is very drony: like a constant machine hum, created by the low infrastructure that consists of electricity cuts, air conditioning units buzzing from buildings, storefronts creating a backdrop to the noise of shopping streets, endless traffic jams and checkpoints, and the pounding beats of folk-pop music from cars and public transport.”

For LazerGazer, the future seems bright for South West Asian & Northern African artists. What excites her are the people and labels that push the boundaries: Liliane Chlela, Flugen, QOW, Assyoutii, Hassan Abou Alam, Abdullah Miniawy, Nour Sokhon, Sefr Records and Bedouin Records—to name a few. But more than anything, she’s excited to see her younger sister leave her mark through her forthcoming music (we cannot wait to hear it).

The 11th instalment of Lentekabinet is nestled between the offroads of Het Twiske. Join us in the two-day affair where you can reunite and reconnect with music, arts, nature and—through all of the above—with each other.