What happens when ritualistic techno, experiments with digital image production techniques, and the delicate exploration of intersectional identities, come together?

Words by Leendert Sonnevelt

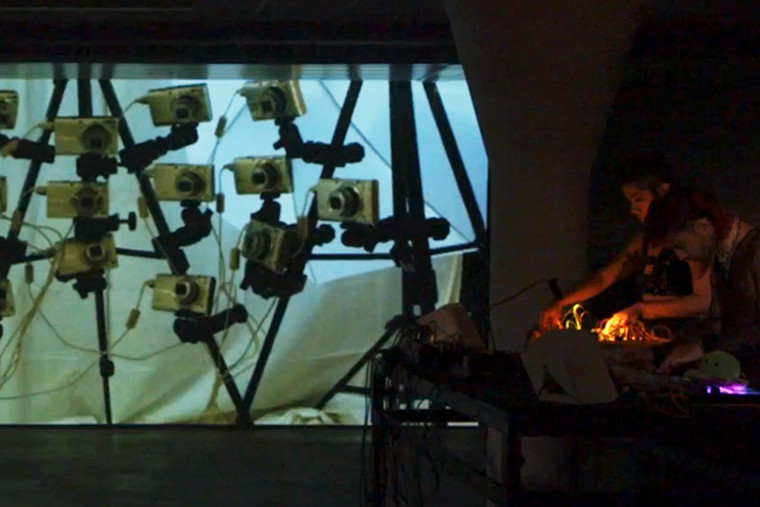

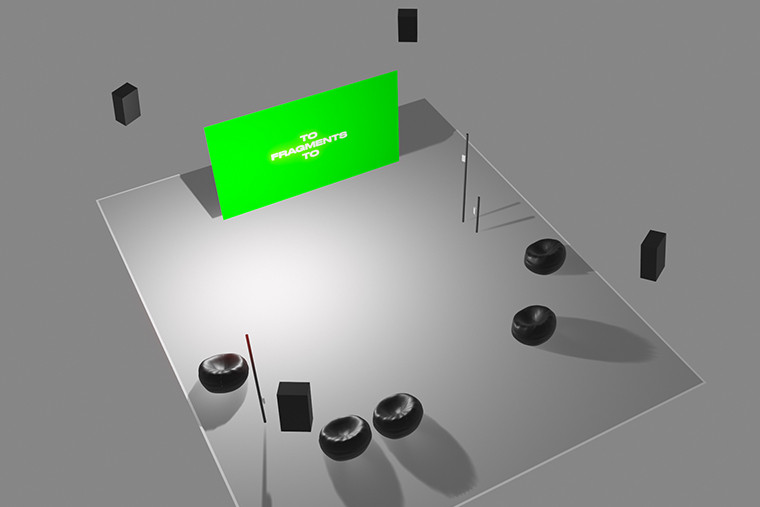

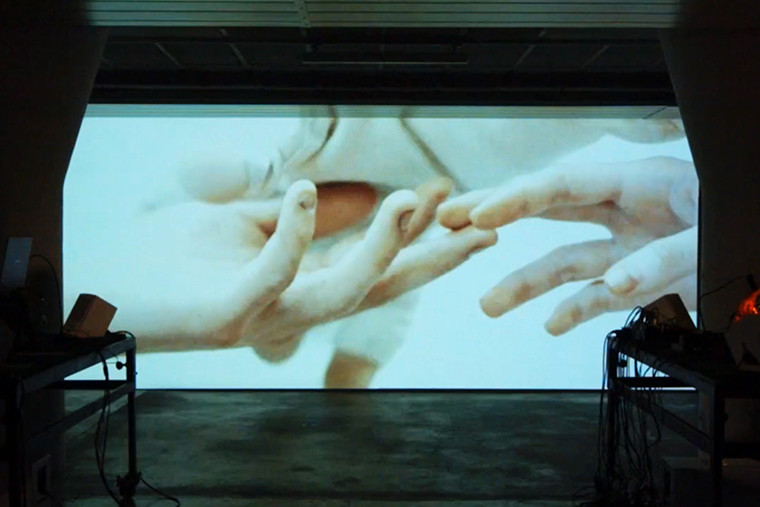

The answer – but equally the question – is CACHE/SPIRIT, an ongoing collaboration between Rotterdam-based producers Linh Luu & Marvin Lalihatu (aka Animistic Beliefs) and media artist Jeisson Drenth. Set to tour the world with their audio-visual liveshow at the onset of 2020, covid forced this forward-thinking threesome to hit ‘reset’. And so, CACHE/SPIRIT evolved from a performance for dark dancefloors into an online artist residency as well as a travelling video installation. At present, CACHE/SPIRIT is all of the above in no particular order; while its gallery set-up is currently on show in Zürich, the output of the artist residency can be explored on DGTL FMNSM.

This week, Dekmantel Connects presents the club performance that started it all: a high-speed, high-tech, high-volume journey into three deeply personal accounts. Here, the artists provide the complex context of their collaborative work; ‘You could just consume CACHE/SPIRIT as it is – and enjoy it – but we really felt the need to explain why we made it.’

Let’s start at the very beginning. How did the three of you meet and start working together? What attracted you in each other, and in each other’s work?

Linh: Jeisson and I met each other first. I was doing sales for a place in Rotterdam, and Jeisson – already working as a freelance artist – was looking for a workspace. I gave him a tour of the building and we started talking. He showed me his work, which I really liked, and we became Facebook friends. From there, we started bumping into each other at events, talking more and more. I showed Marvin his work because I was really excited about it, and we started thinking about doing something together. Later, Jeisson proposed to get together.

Jeisson: I wrote you a very formal email. ‘Good morning. Let’s explore options. Yours truly…’ [Laughs]

Linh, what exactly about Jeisson’s work made you feel excited?

Linh: He was making a video for an event and showed me how he was doing photogrammetry (photography-based 3D modelling). I read about this scanning process before but hadn’t met someone who actually does it. I got really fascinated by the process and the way the work looked.

So, how did you start working together?

Marvin: Our first real collaboration was a music video for one of the tracks on our album, An Eye For AI, in the summer of 2019. We immediately thought of Jeisson to make a work for it and asked if he was down. He was!

Jeisson, what attracted you in the work of Animistic Beliefs?

Jeisson: It’s a gravitational pull. I love the hard, fast energy. I also love the playfulness. They’ve got something… mischievous? I guess ‘provocative’ is not the right term, but there’s a combination of playful, curious and subversive in their persona and work – a dark and a colourful side – and I really like that. Originally I approached Linh and Marvin because I was looking to quit VJing and to start working with artists one-on-one; to add depth to the projects I was working on with artists in electronic music. The video I made for An Eye For AI was an exploration of the concepts of artificial intelligence and computer vision. Our interests overlapped; I was working with algorithms to analyze my face and making art around the results of my DNA test. More generally, I was looking into how technology can be used in self-exploration and how it shapes people’s sense of self. Our first collaboration took these ideas to look at Linh, Marvin, their instruments and physical environment as subjects. It was really inspiring.

After you started collaborating, how was CACHE/SPIRIT born?

Jeisson: I guess that brings us to covid…

Linh: Well, it started right before covid. CACHE/SPIRIT came to be for our performance at Trauma Bar und Kino in Berlin.

Jeisson: Yes, we started working on this non-club project as a solution to our club project being cancelled, due to covid. We premiered the audiovisual liveshow in Berlin but then the other bookings fell through and we couldn’t share it with the people. However, some of the bookings that Linh and Marvin already had were repurposed for other projects – so our CACHE/SPIRIT liveshow started to mutate and fragment into new formats.

Did you initially expect this to be such a multi-dimensional project?

Marvin: No, we always wanted to do something like this but never really took the time for it. It just happened organically; the right people at the right moment.

Linh: The organizations that we worked with presented opportunities for us to make the project grow and develop it into different formats. We were still searching for what we wanted, and they allowed us to do that.

Jeisson: The first (non-club) platform that invited us for a residency was DGTL FMNSM.

Linh: From there, it started shifting shape.

"CACHE/SPIRIT stands for computational memory, on the one hand. ‘Cache’ refers to the location where your behaviour online and in applications is stored. On the other hand, there’s the idea of your spirit or soul. Together, it’s about the human and the technological becoming indistinguishable – reflecting on that and having fun with it, playing with machines"

Let’s zoom in on CACHE/SPIRIT, beginning with the title. What does it stand for?

Jeisson: CACHE/SPIRIT stands for computational memory, on the one hand. ‘Cache’ refers to the location where your behaviour online and in applications is stored. On the other hand, there’s the idea of your spirit or soul. Together, it’s about the human and the technological becoming indistinguishable – reflecting on that and having fun with it, playing with machines. The output is both dystopian and utopian. When we came up with the title, I think we were already subconsciously thinking about looking into the past to shape our future.

Is the project an experiment?

Linh: Yeah, I think it developed in that way. All three of us are very curious and playful beings. We have a lot of different interests and want to test everything.

Marvin: We had a playground wherein we could freely express ourselves.

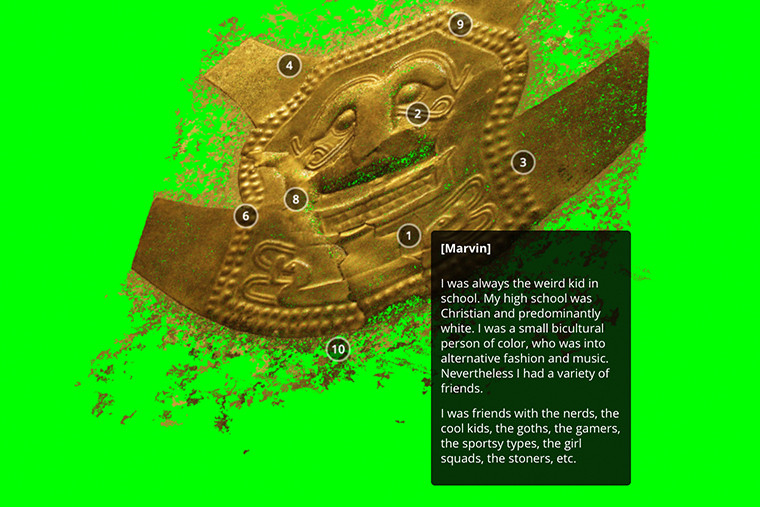

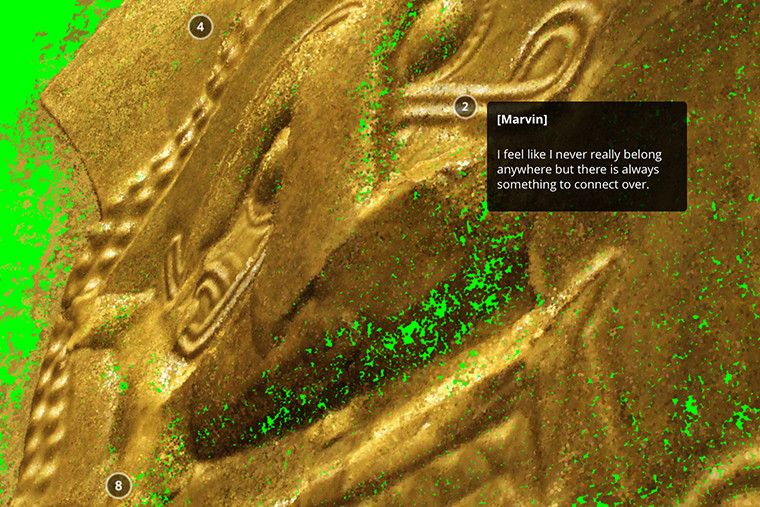

I was browsing through the experimental publications you created as a part of the CACHE/SPIRIT residency on DGTL FMNSM, and there was this beautiful quote: ‘These photogrammetry models represent visual data, yes, but even more so they represent all of our stories combined.’ Can you share how your backgrounds/identities have shaped the work?

Linh: For me it became very clear the moment we created three xpubs. We were at our home/studio, and had a projector up. We were all typing, chatting with each other in a chatbox. We asked each other all these personal and specific questions and didn’t necessarily know each other in that way. There was a lot of overlap in the stories that we were telling each other and we had a lot more connections that we might have expected. It made me feel closer to Jeisson and Marvin, and I felt at home with the three of us. From then on, there was more understanding of each other’s stories – which created a certain…

Marvin: Openness.

It almost sounds like you had to come together to share your stories with each other, before being able to share them in a work. Or, is this work actually the coming together of your stories?

Marvin: It’s a bit of both. We were doing this for the project and to learn from/about each other, but that eventually grew into more.

Jeisson: I think it was a blessing in disguise. This space opened up for us with total creative freedom to do something, supported by people who were interested in our projects. With travel restrictions and the reality of one global crisis after the other, we created something that reflected on current times as well as ourselves, which people could access through their phones and laptops. This projector group conversation, in a way, created a new potential for what we could create and how this could be meaningful to different audiences.

All of you have a very interesting and complex history, and I really appreciated discovering those stories through CACHE/SPIRIT. Can you highlight some of the important personal things that were unearthed?

Marvin: For me, it’s about me and my life experiences; being a biracial, alternative person in both Dutch and Moluccan society. I wanted to highlight that, and how I move in-between these different worlds, never really fitting in. I was a bit of a chameleon in high school, I could fit in everywhere, but never had the feeling of belonging to a specific group. I sometimes still feel like that. I also wanted to spread awareness about my Moluccan culture – its music and identity in general – beyond my own experience. For instance, I used traditional Moluccan instruments and the music of my ancestors: samples, fragments of music from the islands, [traditional Moluccan] Tifa drums, choirs and chants. I tried to use a lot of pre-colonial music in a new format. I also incorporated fragments of indigenous Auyu people from Boven Digoel explaining how they live in harmony with nature, a way of living we seem to have lost the connection with.

Linh: For me it’s mostly an exploration of my own identity. In the past I wasn’t proud to be Chinese and Vietnamese. Because of being bullied when I was younger, I did not want to be that. Now, more and more, I want to make this a part of me. Well, I know it is a part of me but I’m discovering that in certain ways. Being proud, exploring which part of me stems from where, and what things I’ve learned from my communities and places at home, to share that with other people around me. I’ve been reading more on people who are also struggling with this. I hate to say this, but maybe I was actually ashamed to be Chinese. As of lately, especially during covid, I’ve been speaking about this with my parents and asking them about their stories, aside from doing this research on my own. I’ve incorporated this research into the project through vocals, translations and instruments. I feel prouder and prouder of who I am, of the story of my life and that of my parents’ life.

Jeisson: That makes me happy! To be honest, I didn’t know about intersectionality until Linh and Marvin used the word as a digital sticker on top of the recording of one of their live sets. The sticker said ‘Google: Intersectionality’, which was kind of… sassy?

Marvin: It was sassy! [Laughs] There was originally this logo of an alcohol brand, so we put it on top, like: ‘This is more important.’

Jeisson: So, I googled the term. As an adopted biracial Colombian person I am an ethnic minority in the Netherlands, this intersects with my sexuality as a gay man. I’ve experienced intersectionality but never really put words to it. A personal highlight for me with CACHE/SPIRIT is learning about other biracial Dutch people: what is specific to their experience and how we are related, even though our experiences are different. I grew more conscious of different ways by which people are marginalised and how these things are connected. This shift in perspective led to me incorporating things from my process of learning about my ancestry. I visited my home country for the first time in my life last year, which was really intense. In the Netherlands when I talked to people about going to South America all I got was beach holiday and jungle trip stories, and I knew that my experience would be a lot different. Travelling through Colombia I learned about the history of colonialism, pre-Colombian culture, the imposition of the catholic faith and how that shapes gay identity. I walked around thinking ‘Fuck, this is where my parents gave me up’. I felt the pain of my biological parents as well as the joy of my (Dutch) parents who I love deeply. I’m a white European here and in the Netherlands I’m an ethnic minority – how do I make sense of this? What parts of which culture make up who I am and who I can become? The different projects we work on through CACHE/SPIRIT deal with these types of questions. This is something that is of course really complex but that’s not a bad thing, it’s the opposite actually. It’s been great to be able to play and experiment our way through these stories

"What parts of which culture make up who I am and who I can become? The different projects we work on through CACHE/SPIRIT deal with these types of questions"

Linh, something that struck me is how you translated ‘intersectionality’ to Vietnamese – bringing it back to your heritage and leading to a conversation with your father. I understand there’s also Vietnamese poetry incorporated into the work. Can you tell me more about this?

Linh: I translated ‘intersectionality’ for our DGTL FMNSM residency at the time when the Black Lives Matter protests were happening in the US. I was talking about this with my parents and we touched a lot of subjects connected to intersectionality. I found they didn’t really know about this and we started talking. It was a very interesting and urgent conversation.

Marvin: I feel like the whole world was facing this subject at that time – almost a bit like a spiritual awakening.

Linh: When I noticed my parents didn’t know about this, I thought it would be interesting to translate, so they would understand it better. My parents both speak Vietnamese and I didn’t know a lot of political terms in Vietnamese because I was just brought up with the day-to-day language. I first tried to translate it in Google, but the person/computer that reads it to you, speaks in a Northern accent. My family is from the South of Vietnam, so I didn’t know how to pronounce it in the way we would pronounce things. I called my dad and asked him to translate the term, and to say it out loud for me. He asked me what I was going to use it for, and I told him it would be for a song. He didn’t approve of that because he didn’t want me to get involved in making political or protest songs. I hung up the phone and said we’d talk about it later, but he called me back and we had a long conversation. I think he was being (over)protective because of what he went through in Vietnam. In this conversation with my father I learned that he and my grandmother supported the rebels back then, and that they got into trouble – which is one of the reasons they fled. This made me understand why he did not want me to get involved in political things.

The poem I have used in our CACHE/SPIRIT installation touches what I talked about before. The more I talk about the past, even though I first felt my parents didn’t want to talk about the past, the more open they turn out to be. I thought the subject would be painful because it’s part of a trauma. But I decided that I really want to know where I’m from, what actually happened, and what their personal experiences were – in order for me to understand them better. Their traumas are also a part of me and have influenced me in a certain way. Digging deeper into them also means digging deeper into me. My poem in the installation talks about that. I am proud to be their daughter. I am proud to learn more, to know more.

In a practical sense, how are the ancestral practices and knowledge you’ve gathered translated to music?

Marvin: I have tried to re-appropriate instruments and rituals in a new, respectful way. I know what I’m using and how it was used originally. For example, at the start of the CACHE/SPIRIT installation there’s a piece of music with drums and choirs. Those vocals are part of a Moluccan welcoming ritual for people who come into the village. There’s also recordings of Dutch-Moluccan people chanting ‘mena muria’, which translates roughly to ‘one for all, all for one’. There’s also an excerpt from a man from Boven Digoel who talks about his daily life: how they hunt and gather food, living under the shadow of environmental disaster. The pristine rainforest and all its natural resources are being destroyed and replaced by palm oil fields.

Jeisson, you’ve previously referred to the article Does Abstraction Belong to White People? by Miguel Gutierrez. In that article he writes: ‘Who has the right not to explain themselves? The people who don’t have to.’ Can you elaborate on this?

Jeisson: I love this article. It’s dear to me. The quote points towards the ways in which privilege and abstract art are connected. It goes: Who has the right not to explain themselves? The people who don’t have to. The ones whose subjectivities have been naturalized. I think a lot of art is produced and presented around the idea that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, kind of as an excuse to not have to say anything with the work, reflect on society, or maybe also to not deal with the fact that cultural spaces – and club spaces too – are still too often produced for and by white cisgender heterosexual middle-class West European men (and women). At the same time a lot of artists and organisations don’t like to put their faces or names forward too much because they are uncomfortable with putting themselves out there personally like that. But a consequence of this invisibility of people and their ideas – art without words and makers and organisations that choose to hide – is a lack of transparency and a lack of accountability. Art is personal, and the personal is only a-political for those that are really comfortable. The texts in writing, vocals and samples that are used in our projects are not there to really ‘explain’ though. They are there to point towards ideas and stories that are too often erased or deemed unimportant.

"Art is personal, and the personal is only a-political for those that are really comfortable"

Marvin: We want to tell you more about CACHE/SPIRIT because you could just consume the work as it is – and enjoy it – but we really felt the need to explain why we made it.

Jeisson: I’ve worked as a VJ for six years and I’ve always felt intimidated by the idea of having to create beautiful visuals. It’s definitely a love-hate relationship because I love it when something beautiful pops out but I also passionately hate the pressure of design trends and the continuous push of improved computers and softwares with their Hollywood cgi graphics. What has been most exciting to me as a VJ, has always been getting inspired by musicians that have something to say, and also having this big ass projection or LED screen and then learning about what I actually want to use that space for. That turned out to be, studying our relationship with technology from an intersectional point of view. The technologies that surround us, which we have in our homes and in our pockets… all these hardwares and softwares are developed either in the military or in the marketplace – a capitalist context. Technologies are not necessarily designed to create the most human experience. Typically, technologies are extractive and exploitative. But people always find their way to make tech work for them and make the human aspect happen. In lockdown I came across this example of Hong Kong activists that organised virtual protests in social simulation game Animal Crossing (Nintendo Switch). Later, a couple weeks ago, I found out about a group of musicians using the same game to create and present experimental music performances. I love these subversive practices. You can literally see, hear, feel the humanity seep through the cracks – the limitations of technology. Although I don’t see my video work as a form of activism, all images I create have meaning and I do use them to learn about how we can challenge oppressive power structures. For example, with CACHE/SPIRIT I show images of anatomical models that present a binary view on gender and impose the anatomy of young white Western European military men as a standard, (racist and sexist) facial recognition and crowd scanning softwares, cartographic drawings that impose Europe as the centre of the world, renaissance paintings getting shot up by club lasers [laughs], things like that.

"I love these subversive practices. You can literally see, hear, feel the humanity seep through the cracks — the limitations of technology"

You mentioned the use of text in your visuals. It seems like you do this more and more?

Jeisson: Yes, to answer that maybe it’s good to refer to a quote from the artist Rory Pilgrim: ‘As digital and robotic technologies change the fabric of human systems, is it possible to create spaces that unite the human, ecological and technological with basic principles of empathy, care and kindness?’ I think the three of us identify with that quote, and it relates to our process. Along the way we started listening more, reading, sharing and writing more, and as we felt more united texts appeared in our work. Vietnamese first, [English] translation second. The video installation is introduced with a text from the Palace of Inquisition (Cartagena, Colombia), about the practice of othering people. Again: Spanish first, English second. The texts are there to share about our ancestry, to invite different people to identify with the work and for us to find a good balance between something playful and intuitive and something more contemplative.

A club setting, where the three of you perform liveshows, can be a space for critical thought. But it’s also a place where people come to dance, go off, do drugs…

Jeisson: Personally, I go to clubs to release stress and to escape the daily programming of society. This word comes to mind when I think of the club experience: defragmentation – the maintenance of systems [laughs], the reorganising of content to free up space. When you go to the club to do that, to reset, rewire, empty your trash folder I think it’s good to think who actually filled it up. If you’re deprogramming yourself at the club, what programme do you start with? It’s an opportunity to think about your own cultural conditioning and that of others. The texts that artists use in their music, in the studio, in the club, in other parts of their practice, they may cut you, they may affirm you, they may do both – I think that’s great.

"I want to share my personal experiences with people so they can feel less alone than I used to. While at the same time, I would like people to learn from our experiences and our journey"

Why is it so important that your audience – through this interview or other sources – can find or grasp the context or meaning of CACHE/SPIRIT?

Linh: I think it’s important to share the story because it’s such a personal search for the three of us. By sharing our stories and the thoughts behind it, we’ll make it more relatable for a lot of people. I want to share my personal experiences with people so they can feel less alone than I used to. While at the same time, I would like people to learn from our experiences and our journey. It’s an ongoing process; something that changes as the project changes with us. We don’t just want to present the results, but also the journey towards these results, our installations and shows.

CACHE/SPIRIT (LIVE) will be streamed on Wednesday 23 December, the closing day of Dekmantel Connects. The Experimental Publications mentioned can be found here on the website of DGTL FMNSM. Animistic Beliefs and Jeisson Drenth are gearing up for the Dutch debut of their video installation – soon in a museum near you – while their collaboration continues to evolve into future formats.