Words by Christopher Paul

In a landscape saturated with DJ sets, live electronic music performance provides artists with an alternative way of presenting sound; bringing a rewarding real-time presentation of musical ideas, but equally the challenge of becoming a live mix engineer and composer, in addition to performer. Even though real-life music events have come to a standstill, the internet is currently awash with options for people wishing to watch, learn, or perform “live” by way of online streaming events.

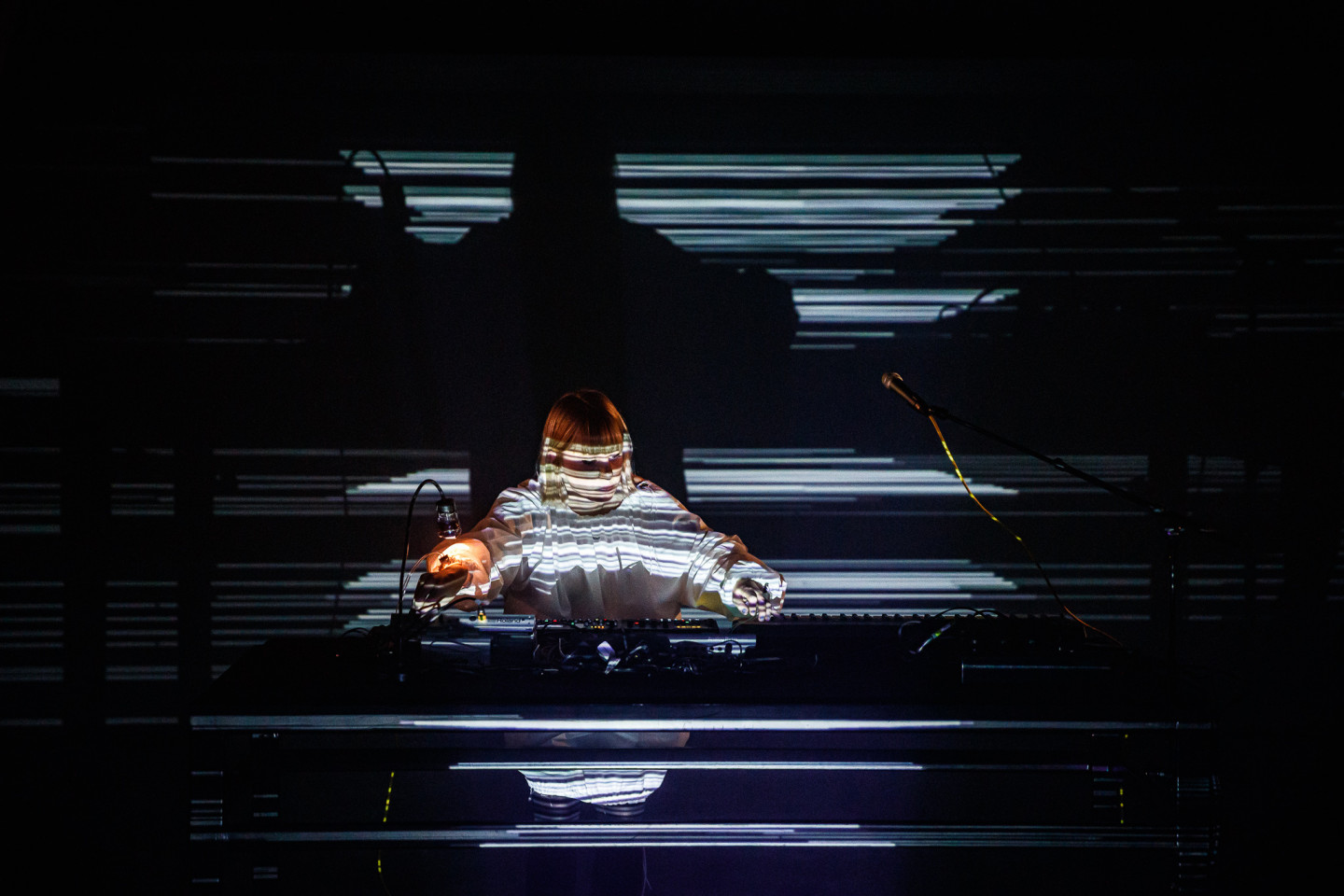

How to go about “building your budget live set-up” is a highly subjective question. It can deliver a myriad of answers influenced by your style of music, your composition preferences, and what “live” even means to a person, something that is a bit of a gray area in itself. This was made evident in conversations we had with analog dreamer Nadia Struiwigh, mind-dancing acid-mistress Alberta Balsam, Brainfeeder’s naïve computer jazz conductor Jameszoo about their live-sets.

Whilst some pieces of gear will inevitably be mentioned through the course of this article, it acts more as a presentation of considerations and workflow perspectives, which can either be used when deciding what it is you need to perform live, or as a way to get more out of what you already have.

What is a live-set, where does one start?

An electronic live-set can broadly be defined as any performance of electronic music live, using music production equipment (samplers, sequencers, synthesizers, laptops), rather than a DJ mix, which uses a media player and mixer to blend pre-recorded audio material.

That being said, the real line between "DJ Set" and "Live Performance" is ambiguous; increasingly so with the popularity of sample services such as Splice, and DJ software and hardware that encourages the use of component audio loops, whether made by the performer themselves or otherwise.

Where our three interviewed artists all agreed was that a key difference is the presentation of music produced entirely by the performer, rather than that of other artists.

Additionally, the last decade has seen a boom in relatively affordable musical hardware, as well as increases in computing power and options of midi controllers allowing more people than ever, as Jameszoo remarks, to “basically make something out of anything”. This tyranny of choice presents its own challenges, like “where the hell do I even start?", "so many manuals" and "damn, I’m gonna need another cable for that".

Two extreme, and in many ways opposite examples of live performances are that of Yves Tumor and Dub FX. For his 2018 performance at the FORM Festival in Arcosanti, Arizona, Yves Tumor performed with nothing more than USB-stick backing-tracks being launched manually from a single CDJ, a microphone plugged into the FX of a DJ mixer and his voice. Dub FX is world-renowned for using a looper pedal, microphone and his voice to create explosive bass music. While purists may cringe at the former’s simplicity; these are both perfectly valid examples of minimalist electronic setups used in completely different ways.

To make the tyranny of choice a bit more digestible, I identified two questions one could ask themselves when wanting to build a performance setup, the combined answer narrowing down the number of possible approaches: Continuous performance, or concert-style performance? Preparation or improvisation?

A continuous performance is similar to a DJ set, where each composition flows seamlessly into another, contrasted with a concert-style performance, where there is pause (for applause) between songs. Preparation can either refer to the use of pre-sequenced or pre-recorded sound elements, or the practice of composed music, and improvisation is the total opposite; making everything up as you go along.

These are not black and white, as many a live-set contain elements of continuity and pause, studio preparation and “on the fly” improvisation.

Preparation & improvisation

For Nadia Struiwigh, preparation revolves around the programming of patterns and sequences beforehand, where the tweaking, blending and mixing of sound levels and effects takes centre-stage in terms of the performative offering. By doing this, also with the ability to change whatever she has prepared in real time, no two sets are ever the same. By doing this, also with the ability to change whatever she has prepared in real time, no two sets are ever the same.Alberta Balsam’s approach is similar, with the occasional addition of her own vocals. Both their approaches are very much in line with the principles of Dub mixing, pioneered by Jamaican producers such as King Tubby, Scientist and Lee “Scratch” Perry; where loops of audio are mixed and manipulated live through a mixing board and various effects units. As the poet Mutaburaka said, "Dub is where the engineer becomes the artist”.

These producers’ mentality, and their influence on the Soundsystem culture of 1970’s Jamaica, laid fundamental ground-work for both DJing and electronic music production as we know it today. For example, the clip-style launcher in Ableton Live and some modern grooveboxes is directly influenced by these principles.

In stark contrast, Jameszoo approaches his performances from a perspective more familiar to traditional instrumental performers, Jazz in particular. When performing with a live band, he takes on the role of bandleader, delegating various instrumental duties to skilled session musicians, where his compositions are interpreted in a more traditional concert setting. Playing solo live shows, his inimitable approach is firmly rooted on the improvisational end of the performance spectrum. Aside from the use of a looping device, his setup is in a constant state of flux, changing every time. This requires the dedication to practice of a skilled instrumentalist, and an intimate understanding of the sounds your chosen equipment can produce. Suffice to say, Jameszoo has had a lot of practice on a lot of equipment.

From studio to stage

Many producers will be looking for a way to port their existing production ideas to a more performable context. There are various ways of achieving this, the combination of Ableton Live on a laptop and an Akai APC controller likely being the most ubiquitous example. Whilst it’s not exactly cheap, Elektron’s Octatrack deserves special mention here for being one of few pieces of hardware that can store and playback large quantities of long audio files simultaneously without having to stop the machine and change project, 1010 Blackbox being another. Sam Barker, Fjaak, and Surgeon all have videos online showing different approaches to going from studio to performance using the Octatrack. Barker’s method of sampling different chords from his synthesizers into single audio files, which he then sequences back in slices, is particularly genius. Alberta Balsam also cited the Swedish-built sampler as being a crucial piece of equipment that ties her performances together. At time of writing, in the Netherlands one can score a second-hand MKI for 600 euro, which is half the price of the latest iteration with no significant difference in functionality.

"When I’m playing more of a peak-time environment, I use heavier kicks with simpler patterns, but in a calmer venue or in an opening set, I use less aggressive bass drums to suit the setting." - Alberta Balsam

Levels, levels, levels!

One thing that does apply to all approaches, regardless of what you use, is that of the mix. What often separates a live electronic performance from a more traditional instrumental offering is that in most cases, unlike an instrumental band, the performer does not benefit from a venue sound engineer having detailed control over every individual sound. This is crucial. It means that when not careful, that banging kick you wanted to bring in on the next track could have no impact at all, or that ostensibly soft snare you programmed could blow up the sound-system and damage the ears of your audience. Struiwigh observes “compared to DJing, where you’re blending finished recordings, live performance has far more variables to take into account, which also makes it a lot more taxing, mentally. In that way, I feel live performance is more of a presentation of the soul; it’s a lot more introspective and I have my head down most of the time, whereas a DJ set allows for more audience communication. This amount of concentration is maybe also why live performances tend to be shorter than DJ sets”, she explains, while jokingly referring to an exception of the rule being Octave One’s Electribe-fuelled marathons.

In my prior experience as a sound engineer, I’ve observed volume control to be the most common challenge that live performers face; the volume levels of individual sounds often being a make or break factor in how well a show translates. It’s on this topic that Alberta Balsam had a few interesting pearls of wisdom to share. With the assistance of a decibel meter, Balsam meticulously levels all of her kick drums as preparation, in order of intensity, to avoid the afore-mentioned volume-mismatches between tracks.

With sounds that are more atmospheric or less percussive, there is a bit more leeway for setting volume levels on the fly, though when dealing with foundational elements, this approach can go a long way in providing a consistent dynamic to your set. Taking things a step further, Alberta always sequences her prepared kicks live on a separate device from the rest of her drums. This affords two advantages: the first is that it allows for more fluid transitions between compositions; the kick sound and rhythm can be changed independently of all other percussion and vice-versa. More interestingly though, it allows her to change the mood of her compositions significantly, “When I’m playing more of a peak-time environment, I use heavier kicks with simpler patterns, but in a calmer venue or in an opening set, I use less aggressive bass drums to suit the setting”.

Blending into the flow

Both Alberta and Nadia espouse the use of slowly blending elements, and keeping things sparse. “Try not to have everything playing at once, on a loud sound-system it’s easy for things to get too hectic and cluttered. This way your tracks also maintain interest for longer”, advises Alberta, and in reference to when changing patches on a synthesizer, “always take elements out of the mix before changing sounds.” Indeed, some synthesizers, particularly the analog variety, can create a jarring sound when transitioning between patches, due to abrupt changes in oscillator, amp and envelope settings.

For those attempting to build continuously flowing sets, how to transition between compositions will also be something important to consider. When using multiple sound-generating devices this can be as simple as blending one sound out whilst the other remains, and repeating the process, though if you only have one sound generator, or are seeking more variation in transitions, time-based FX units (Delays, Echo’s, Reverbs) and loopers can be very useful. An essential tool Nadia Struiwigh mentions is the use of an “ambience layer”, in her case putting a monophonic synthesizer through a reverb effect, adjusted to create spacious soundscapes that can hold their own in less busy moments of the set, as she prepares the next elements to mix in.

Alberta Balsam achieves similar results using a Kaoss Pad, additionally using its looper function to create short repeating phrases in real time. All three artists agree, loopers are a powerful way to achieve continuity during a set. With some skill, intricate performances can be realized from little more than a single sound generator (laptop, modular synthesizer, voice, spoon and bucket, take your pick) and a looping device; Mark Rebelliet’s performance in Amsterdam’s Paradiso is a humorous testament to the power of this approach.

Similarly, running a cheap drum machine or groovebox through a handful of guitar pedals (there are a crazy amount of these available for under 100 Euro) can create infinite combinations of texture and tonality, keeping the sound varied. Again referencing Dub terminology and the Yves Tumor approach, there’s one instrument that every club, most venues with a sound-system and maybe a friend of yours has, and that is a mixer. Club DJ mixers usually have an equalizer, filter, and sometimes an FX section, and as Four Tet has shown, there are no rules saying one has to put records through those 4 channels.

Larger venues will have access to full-format mixing consoles, which may allow you to achieve a greater level of fidelity and hands-on control than you are capable of in the bedroom studio.

"Try not to have everything playing at once, on a loud sound-system it’s easy for things to get too hectic and cluttered. This way your tracks also maintain interest for longer." - Alberta Balsam

Final tips

Towards the end of our respective conversations, Nadia Struiwigh, Alberta Balsam and Jameszoo gave answers to one of those handy cliché questions: “Do you have any advice for people wanting to experiment with live performance that you wish you’d known starting out?”

"Ask people for help if you don’t understand something! Try a lot of stuff, manuals don’t have all the answers, and make sure you practice a lot and prepare well. Always have backups where possible, and make sure to take all the time you need setting your levels properly during sound checks before the show" are Nadia’s tips, with Jameszoo adding that when playing alongside live musicians like drummers, make sure the stage monitors are set in a way you can still hear each other and what you’re doing.

Alberta said “Practice with a dB meter, especially with bass sounds. Keep your setup simple and effective. It’s a good idea to have “safety zones” set up that you can revert to if things get hectic, and try to include gear you can actually “play” with your hands or feet to keep things interesting.”

"Ask people for help if you don’t understand something! Try a lot of stuff, manuals don’t have all the answers, and make sure you practice a lot and prepare well. Always have backups where possible, and make sure to take all the time you need setting your levels properly during sound checks before the show" - Nadia Struiwigh

Jameszoo’s advice came on a philosophical level. Earlier in his career, he felt obligated to perform live, but in hindsight concedes that he may have rushed into the process for the wrong reasons. He stressed that as a DJ, doing live sets because of the perceived increase in profile isn’t the best motivation, and it’s something one should take their time with, making sure they feel comfortable with what they’re doing before taking it to the stage. After all, there’s nothing wrong with just DJing your tracks either; it may be more efficient in the context of what you are presenting. “Make sure you’re having fun, most of all!”

Signing off with a few handy final resources; Nadia Struiwigh will be sharing live-streams through her Twitch channel, where you’ll be able to tune into and rewatch how to’s for both Ableton and various hardware. She is also a part of the development team at Lens-Live, a free service which aims to take the technical hassle out of setting up a stream.

Happy Jamming!

Photos by Bart Heemskerk (Nadia Struiwigh + Alberta Balsam) & Yannick van de Wijngaert (Jameszoo)