Adam X might be sat in his Berlin flat, gazing out of the window at the hazel and alder trees that are making him “delirious” with seasonal allergies, but his heart will always be in New York City. It was there he was born in 1971. It was there he grew up "besides the train tracks" and went on to become the police’s most wanted graffiti artist in 1989. But most importantly, it was there that he built New York’s first techno scene with older brother Frankie Bones.

Words by Kristan J. Caryl, Photo's provided by Adam X

That was a long time ago now, but in a thick Brooklyn accent, Adam Mitchell effortlessly recalls the sights, scenes and sounds of the nineties as if they were yesterday. His passion is infectious; the details obsessive, and his love for the borough burns strong despite it being where his father was murdered while out driving a taxi in 1984 and where the brothers were once walled up by police who mistakenly thought they were dealing drugs.

“When I would get on the subway in the middle of summer in New York, I could smell the tar coming off the railroad tyres that hold the tracks,” he remembers. “It's really unique, so if i smell it somewhere it immediately takes me back to that period.”

It was a time of economic recession in New York. The streets were “grimy,” there was lots of racial tension and increasing police pressure. Adam had been escaping it all by spraying trains as often as he could. A key protagonist in the New York graffiti scene under the name VEN and as a member of the legendary A.O.K. crew, he eventually became too well known and realised he was heading for jail if he didn’t give up.

Around the late eighties, he says the art scene had become increasingly violent and gang related. Friends were getting stabbed. Adam was “always in it for the art, writing and getting up” so wanted out. At the time, music was background noise—early rap and electro, Eric B & Rakim, C-Bank, Black Sabbath, the disco of his parents—but he knew that somehow getting involved with it on a deeper level was a route out of trouble.

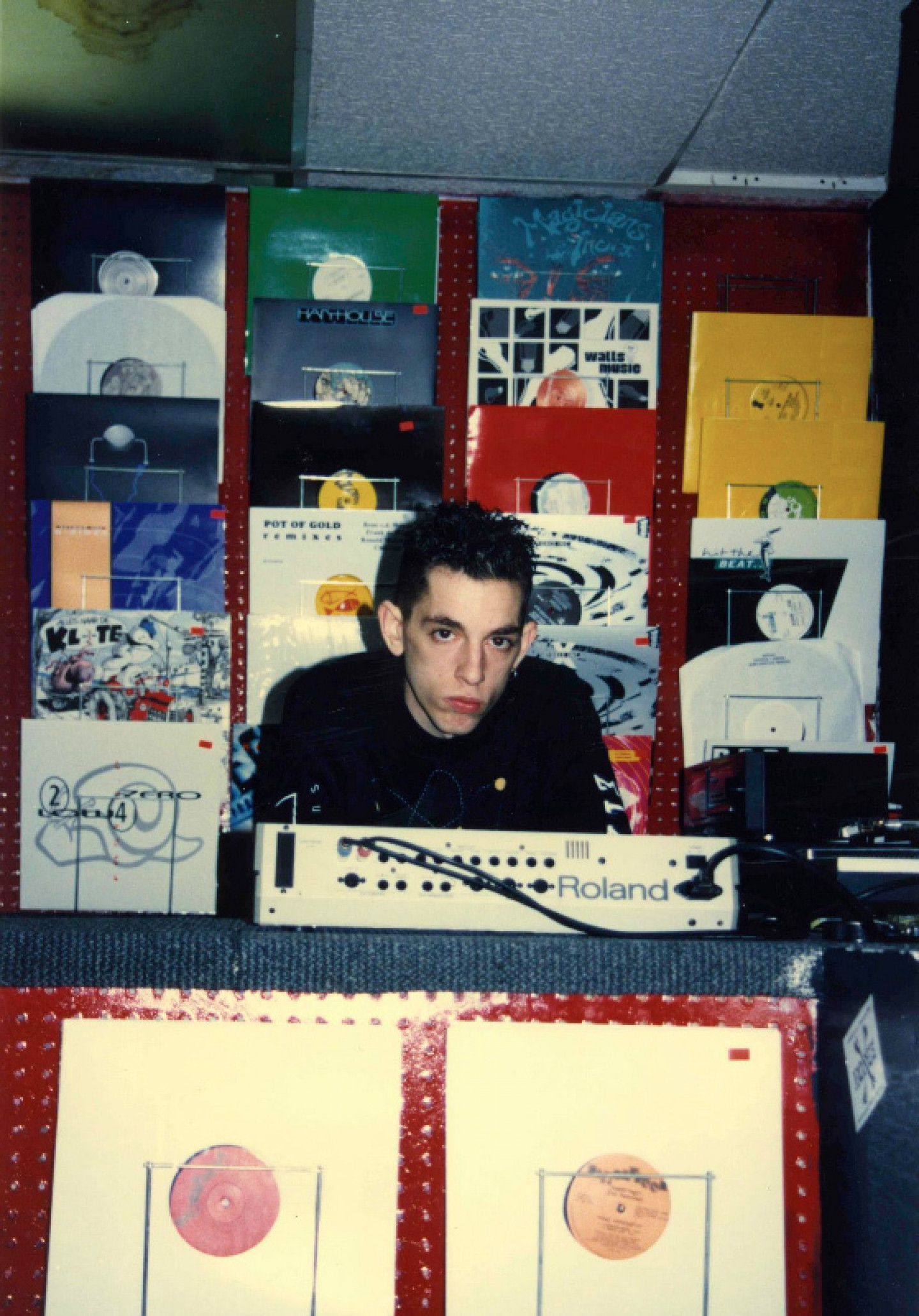

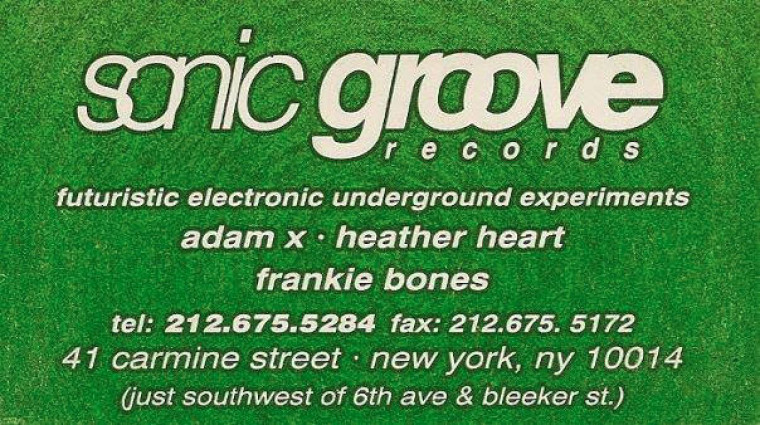

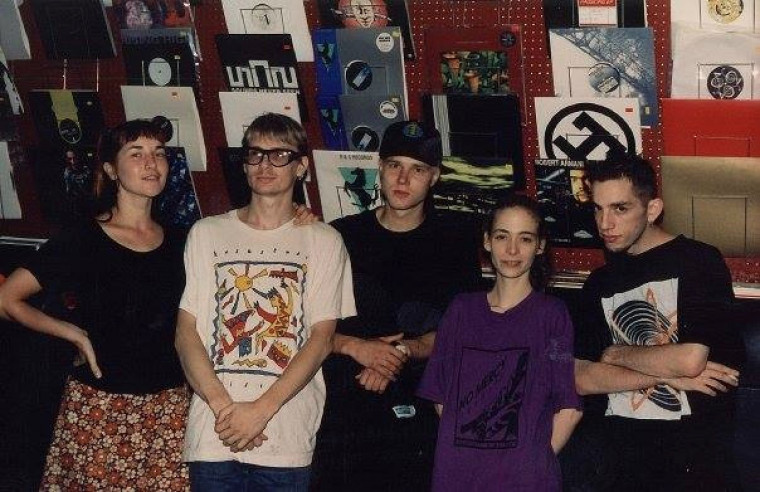

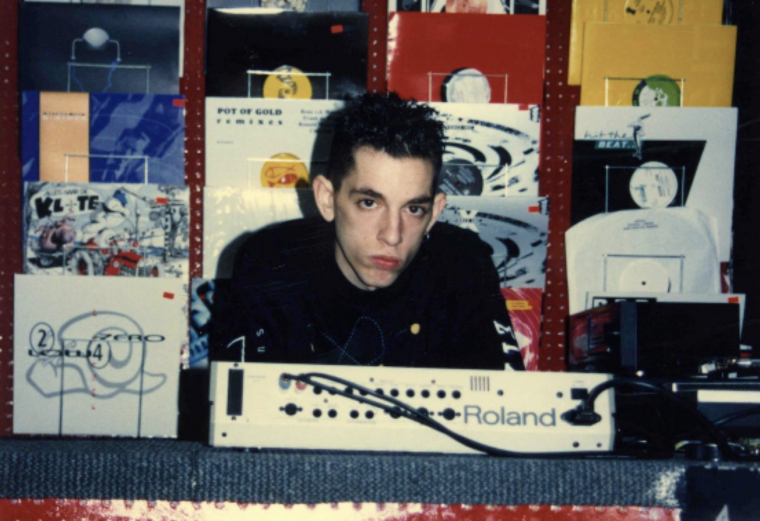

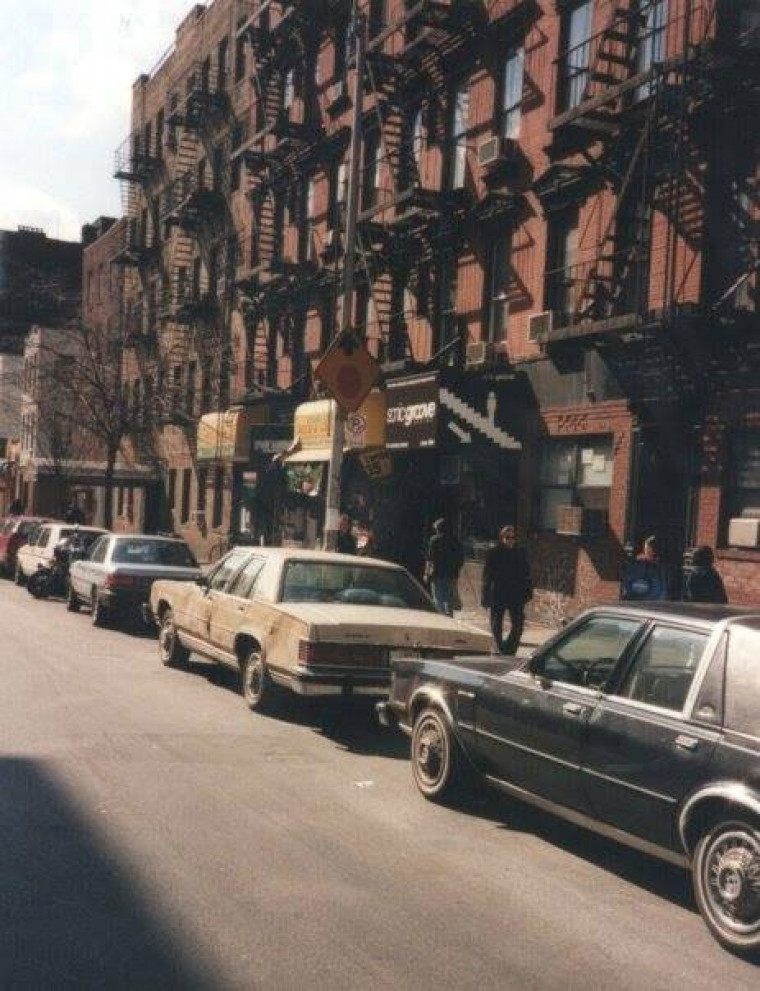

When his brother opened Sonic Groove Records along with Heather Heart (who ran the legendary Under One Sky fanzine ) in Brooklyn in early 1990, it was the perfect excuse. Adam started working behind the counter and the shop was soon a success.

“I remember listening to Belgian techno in 1990 thinking, ‘why is this so dark? Is it full of cathedrals and rain and gloom and medieval scenes over there?’” he says from his Berlin flat. “Now I can see the same Gothic cathedral churches out of my window. The music really connected with us. Super dark techno was our shit back then. 1990 is my favourite era to this day, nothing surpasses it.”

At the time, there was no techno scene in the city at all. Joey Beltran was making it, and the house DJs would occasionally play ‘Strings of Life’ or ‘Rock to the Beat,’ but there were no parties. “We stocked those records in the shop, and we sold the obvious stuff from Snap and C&C Music Factory to get people in, but then we pushed European and Detroit techno on them, and no one else was doing that. By 1991, we were pure techno, we didn’t even stock house music.”

With more and more people buying into what they were hearing, it was only a matter of time until it made sense to throw a party. The first one Adam and Frankie were involved with was in a small apartment in Brooklyn. The tenant emptied all his stuff out and 60 people piled in. “Everyone was on E, which was a new thing in New York. It worked hand in hand with techno so people had like a religious experience.”

Word soon got round and the techno secret was out, so before long the brothers were renting generators and heading up to the train tracks Adam knew so well from his spraying days.

“It was a pretty abandoned area. We did parties isolated from residential housing and we knew the police couldn't get to us ‘cause there was no roads to get back there. We’d cut the fence in the subway yard four kilometres away down the tracks ‘cause I knew they had these work carts you could put together, take out of the subway yard, through the fence, onto the tracks and push them all the way down like dolly trucks. We’d carry the sound system up the hill, put it on the cart and push it into the middle of this industrial area in these junk yards.”

Crowds were initially two to three hundred people strong. At the time, the baggy fashion of the Castlemorton raves or Madchester scenes hadn’t quite caught on, but Frankie did bring back hoodies from his Summer of Love gigs in the UK and Adam was quick to lift them. “People just came dirty, ‘cause you were gunna get dirty in the middle of fucking nowhere.”

Word of the parties spread through Frankie’s college radio show in Brooklyn. He’d tell them to come to the shop and get a map, then head to the secret locations together. “Nobody outside the circle knew it was going on. It was so new back then,” says Adam, who reckons it was mainly white, Latino and Puerto Rican people at the raves. “Very urban, very street people, very Brooklyn, New York City street kids.”

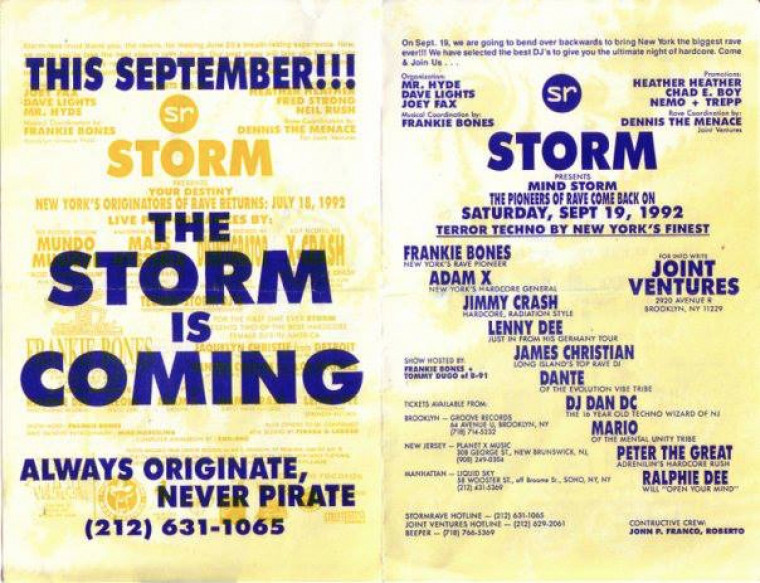

By 1992, they were pulling crowds to the junk yards that were attracting the wrong attention, so threw a bigger party—the first “proper” STORMrave—on Staten Island. They got permission to use a warehouse, but it was still illegal to gather so many people without a permit. Fortunately, amongst the ravers were people connected to the fire and police department, “so if they came, they didn’t bother us.”

Still growing quickly, they decided to move once again within a year or so. “We stepped in too far,” rues Adam. “We did a party in Manhattan near Limelight, who were big competition. We had a lot of drama with promoters. They had my bro set up, had mafia guys beat him up and pistol whip him outside his house.“

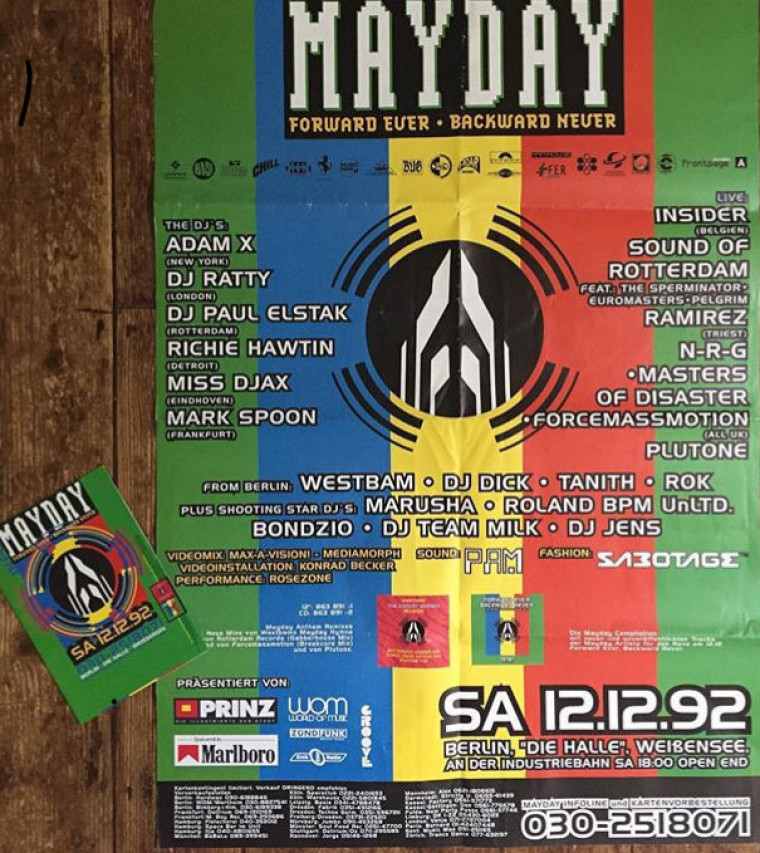

At this time, Adam and Frankie always played, but so did Jimmy Crash, Richie Hawtin, and Sven Väth made his US debut. Doc Martin came from the West Coast. Beltran played. A young Moby even used to write in to the Under One Sky fanzine before eventually going on to play the STORMraves himself.

The techno was fast, around 140bpm and upwards, but changed rapidly in those years. Every few months "it took on a new flavour," which is part of what made Adam love it so much. He played “acid, hardcore, crazy 160bpm 303 tracks, hard Detroit techno” and reckons you could really tell exactly where each record came from.

“There is a New York sound that was different to Detroit, Belgium, Germany. Back then sounds had more regional favours. New York was more freestyle, broken beat shit. I liked the hardness and darkness of it, metal on metal. The mechanical sound of the train on the track is rhythmic and industrial and reminds me of painting in the tunnels. I played in junk yards as a kid, so to me industrial music makes most sense to the person I am. It was the soundtrack to my everyday reality.”

As a producer he was making similar styles. Turned off by the heavily sampled rave sounds coming over from Europe around 1992, he bought his own hardware and started making raw tracks with his 808, 909 and 303. “Around 94/95 everyone was doing it so I gave up, “ he says. "I then stripped it down, made tracky, hard, minimal stuff.” When that got out of control he turned to his “infinite love of Sheffield” and experimented with bleeps and bass. “We just wanted to expose people to good music, and techno is about going forward so we wanted to keep it moving.”

During the nineties, Mayor Giuliani was cracking down hard. The city had been in a financial crisis for 30 years, the murder rate rose from 1550 people in 1985 to 2200 by 1990. Adam says he was a blessing and a curse. “He destroyed nightlife, destroyed the culture, really fucked it up, like, terrible,” but admits previously no-go areas like Times Square were much safer by the end of the decade, and that the murder rate had fallen to the 300 mark.

Raves were strangled by a few factors. In order to cut down on the rising crack epidemic, it was ruled that property speculators who owned the derelict buildings where deals went down were suddenly responsible for what went on in them and risked prison if they didn’t act. Another factor was the Social Club Task Force, set up after one of the worst fires in New York’s history was started when a molotov cocktail was thrown into a bar to settle a dispute. 88 people were killed. From then, all illegal parties were being investigated in earnest and the pressure was building.

The third factor was a TV special by popular news anchor, Peter Jennings. His 45 minute report, Ecstasy Rising, convinced the public and everyone else that raves were about dealing drugs. Local governments ordered police forces to crack down on the so called “drug movement.” This brought about a real collapse in 1998/99 that meant raves went from being in “40 of the 52 states” to just about nowhere.

Adam dialled back his operation from 5000 people events to word-of-mouth parties for around 500 “hardcore heads” that he says were some of his favourite ever. They used parking garages, warehouses in Williamsburg and abandoned locations. The vibe was utterly DIY, the sound systems were always “fucking great” and the tempo of the techno was around 140bpm, but very specific in style. “There was loop techno like Adam Beyer, Regis and Surgeon, or wonky stuff from Vogel, Neil Landstrumm and Si Begg. Scenes are much more connected now, people are more open, the way it should be.”

They eventually fizzled out as the record store grew busier, people from the raves went off to set up their own events and legal venues began being used, even including federal government spaces like the armouries where the national guard would store tanks to be used in the event of a national disaster. Adam often booked the line-ups at these—plus a rave in a football stadium on Randall’s Island where Electric Zoo is now held—bringing in people like Dave Clarke, Electric Indigo, Dan Bell, Robert Hood and DJ Skull.

“It was an amazing time and life was going so quick," beams Adam. "I’m so proud we built the record store business from nothing. I didn’t come from money, nobody gave me shit, every dime and dollar I earned I saved and invested. I’m a Brooklyn street kid from a proletarian father. We were doing it, living the dream.”

What finally took him away from the city he loves was 911. Up to that point everything was “fucking peaches and cream.” But Sonic Groove Records was located a couple of kilometres from ground zero so was shut for two weeks after the attacks. “It was like a war zone,” he remembers. Because of this, the tourists who made up 50% of the clientele stayed away. Then the euro came in and the dollar tanked against it so European imports, which made up most of the shop’s stock, went from $10 to $14 over night. Then, high speed internet arrived so people started buying online, and the first digital DJ software started taking off. “We were done. The scene was nonexistent.” The shop finally closed its doors on October 27th, 2004, almost 15 years after first opening.

A brief job renting apartments in 2005 followed, then in 2007 Adam head to Berlin to start the next chapter, but the legacy of the STORMraves and record shop lives on in the Sonic Groove label he continues to run.

Somehow, history often leaves out the importance of the New York scene. “We were the black sheep of techno” says Adam, who for twenty years now has been driving the industrial and EBM scenes forward. “I will eat, sleep, live this shit to the day I fucking die."