Dark matter, an invisible substance that comprises about 27 percent of the universe, remains one of the most perplexing mysteries in modern science. Though scientists cannot observe it directly, its existence is inferred through the gravitational pull it exerts on the matter we can see. Despite decades of research and increasingly advanced detection methods, the true nature of dark matter—both in our atmosphere and across the cosmos—continues to elude physicists, driving ongoing efforts to understand this fundamental piece of the universe’s puzzle.

By Isabella Ubaldi

Photos: Jeroen Verrecht (installation) & Stef van Oosterhout (festival)

Matière Noire is a Parisian design studio that operates at the intersection of art, architecture, and engineering, drawing inspiration from the very concept of dark matter. The notion of working with the intangible is central to the studio’s ethos, where design transcends aesthetics to create immersive atmospheres that are as much about emotion and ephemerality as they are about space.

Founded by Pierre Dagba and Felix Ward, the studio balances a dual approach where one side focuses on commercial work in fashion, arts, and music, while the other acts as a laboratory for experimentation and collaboration with engineers and architects. This blend allows them to create projects that are both technically intricate and emotionally resonant, where the complexity of their design process results in experiences that straddle simplicity and power.

Their work on both the UFO I and UFO II stages at the 10th anniversary of Dekmantel in Amsterdam was testament to their ability to merge technical precision with artistic expression. Described as dystopic and evolving, Matière Noire undertook the task of completely redesigning UFO I and UFO II under the guidance of Dutch electronic music legend — Albert van Abbe. In this Q&A, the co-founders delve into their creative journey, their collaborative process, and the projects that continue to shape their evolving practice.

Can you tell me a little bit about your studio and your practice?

Pierre: Our studio is currently in a transition phase. We have a commercial side that covers the fashion, arts, and music industries, and another side that operates as a laboratory—a field of experimentation with engineers, architects, and designers. The idea now, which feels very relevant at this moment, is to merge these two concepts. We’re mixing the experimental practice with fashion show artistic development, and this is a complex field to blend. Yet, the exciting part is creating some kind of hybrid profile in the process. Our new view involves combining an engineer’s vision with architectural experience. It’s exciting because we have a very particular profile. The next step is finding conceptual, philosophical mindsets because, for us, the most powerful thing is to start with a word or just an atmosphere.

This is why we talk about atmosphere design. It’s not just about the design of architecture or even pure design; it’s about creating a complete atmosphere. The most important cue is the concept of time—whether that’s movement or the perception of time as people walk into the space. Designing around time is very central to our process.

Felix: We come from different backgrounds and have complementary approaches. I have a background in design and scenography, but I didn’t formally study it. I’ve always been surrounded by arts and music, and I grew up in that environment.

Pierre: My background is different. I started in merchandising and technical building, learning those practices early on, and later attended a Space Design school. During this time, I worked in a club as a light engineer. When Felix and I met, we combined overall artistic creation with specific activation—being super specific with lights, materials, and structure. We have this paradoxical approach of being both macro and micro about the design.

Felix: That’s what makes the studio very hybrid, and clients sometimes have trouble understanding that we can do light design, scenography, and architecture individually or all together. Our work spans from conceptual processes to very technical, advanced elements. We have two conceptual antennae: one for research and conceptual work with no brief, and the other for more commercial projects, which are often informed by our experimental work. For example, here at Dekmantel, we allowed ourselves a lot of experimentation, which can then feed into commercial projects.

Pierre: This hybrid situation allows us to explore our differences, building on the idea from John Divola: “the simple expression of a complex thought.” We like having a simple, pure, emotional idea and then putting a lot of energy into development and prototyping. The final result is something pure and sharp, with an ambiguity between the emotional and the technical.

Felix: Often, we find that the simplest things are the most powerful.

How did you meet?

Pierre: We met about three and a half years ago through a mutual friend. A few months later, that same summer, we decided to start the studio together. During that time, I evolved into being a more hands-on designer. What helped us move quickly was our unorthodox approach to design and materials. We often use sets and fixtures in unconventional ways, which has propelled us in both the commercial and artistic worlds. Our aim is always to create lighting design that’s never just lighting design because light and space are inseparable.

Was there an overarching theme to your work with Dekmantel this year?

Felix: The concept is based on the transition of time from day to night. Dekmantel has several festivals throughout the year, and this one in Amsterdam occurs when the sun is highest. The day-to-night concept is based on the movement of the sun.

How did your concept feed into that?

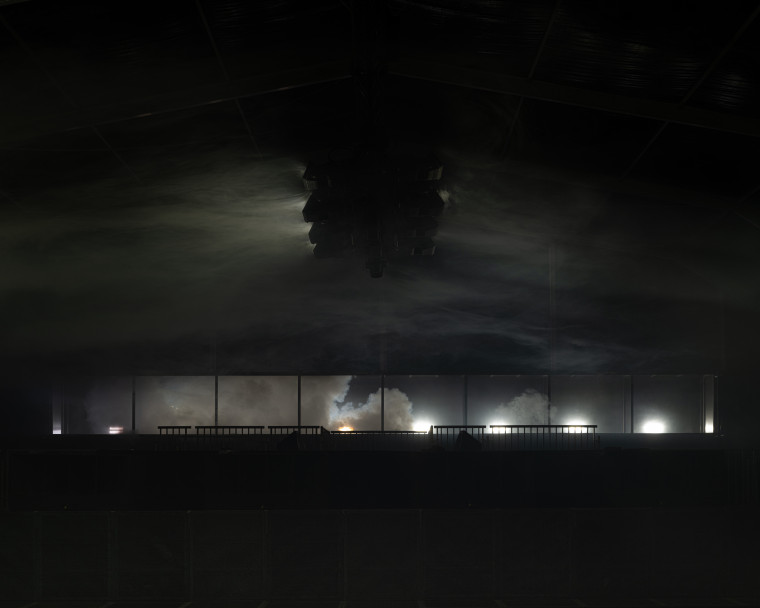

Felix: Dekmantel in Amsterdam Bos represents the highest point of the day, which for us meant intensity, heat, and movement. The [concepts of the] UFO I and UFO II [stages] were connected, but UFO I was the bigger installation. We worked with the idea of containing an energy source that translated into lights but didn’t necessarily come from an energy source. Essentially, we created a long, panoramic custom-made box made mostly of glass. Within that box, we used various effects to create a lot of light in the background of the stage.

Pierre: The idea was also to contain something that’s based on entertainment, which explains the fireworks, flames, and pyrotechnic elements. We like the idea of trying to contain this kind of fire and rage that comes with pyrotechnics, putting it into a small fixture.

Felix: We thought about containing fireworks inside a 1 metre x 1 metre x 1 metre box, which normally would explode 300 metres high. [We asked ourselves], “What if it was contained in a box, and you could see what was happening inside?” The contrast with the power of lighting inside the box mirrored the intensity of the sun. We also included flamethrowers contained in a glass box, which were behind the stage. The idea was to create something that altered spatial perception, with elements like smoke, panels, and sparklers that changed how the boxes were perceived.

Pierre: Our idea was to create an atmosphere that moves around you, not just one you move into. The massive amount of machinery on rails above the crowd changed the perception of the space. We aimed to push the limits of what’s possible, adding smoke so that people experienced not only the atmosphere but also its movement.

How have you incorporated your background in club and light design into your work at Dekmantel?

Pierre: Custom club designs are really how Matière Noire started, and we’ve always kept a foot in music through lighting design. Our connection to this music scene allows us to maintain a balance between being a guest and a designer, which is crucial for creating a subtle yet impactful experience.

And how did you apply your multidisciplinary approach to the UFO stages?

Felix: Our work is characterised by a hybrid design that combines technical and artistic elements. For Dekmantel, this came together in the most challenging part of the project: the glass box in UFO I. It needed to be designed for three editions and with future adaptations in mind, which I can’t disclose yet. It also had to be engineered to contain heat and smoke while providing easy access to reload the different analog effects within it.

What environmental considerations did you have to take into consideration?

Felix: The biggest ecological concern was the energy source. Most of the stage was made from rental equipment, and the only build-out, the glass box, will be reused for at least two more editions and potentially as an installation piece.

What are some of the unexpected challenges when designing for a festival as opposed to an indoor club space?

Pierre: The main challenges are setup time and budget because it’s an ephemeral installation. Unexpected challenges often relate to light and pyrotechnics programming and how those two elements coincide.

Finally, how do you balance designing a space with additional elements like pyrotechnics and smoke while ensuring they don’t detract from the sonic experience?

Felix: This subtlety was achieved in the programming and live operation of the lights. Our deep connection with this genre of music helped us to accompany it rather than overpower it.

Dekmantel celebrates its 11th edition in 2025. Pre-register here.