What do electronic music and biology have in common? Tons, if you ask Tijmen Blokzijl – better known as Teqmun.

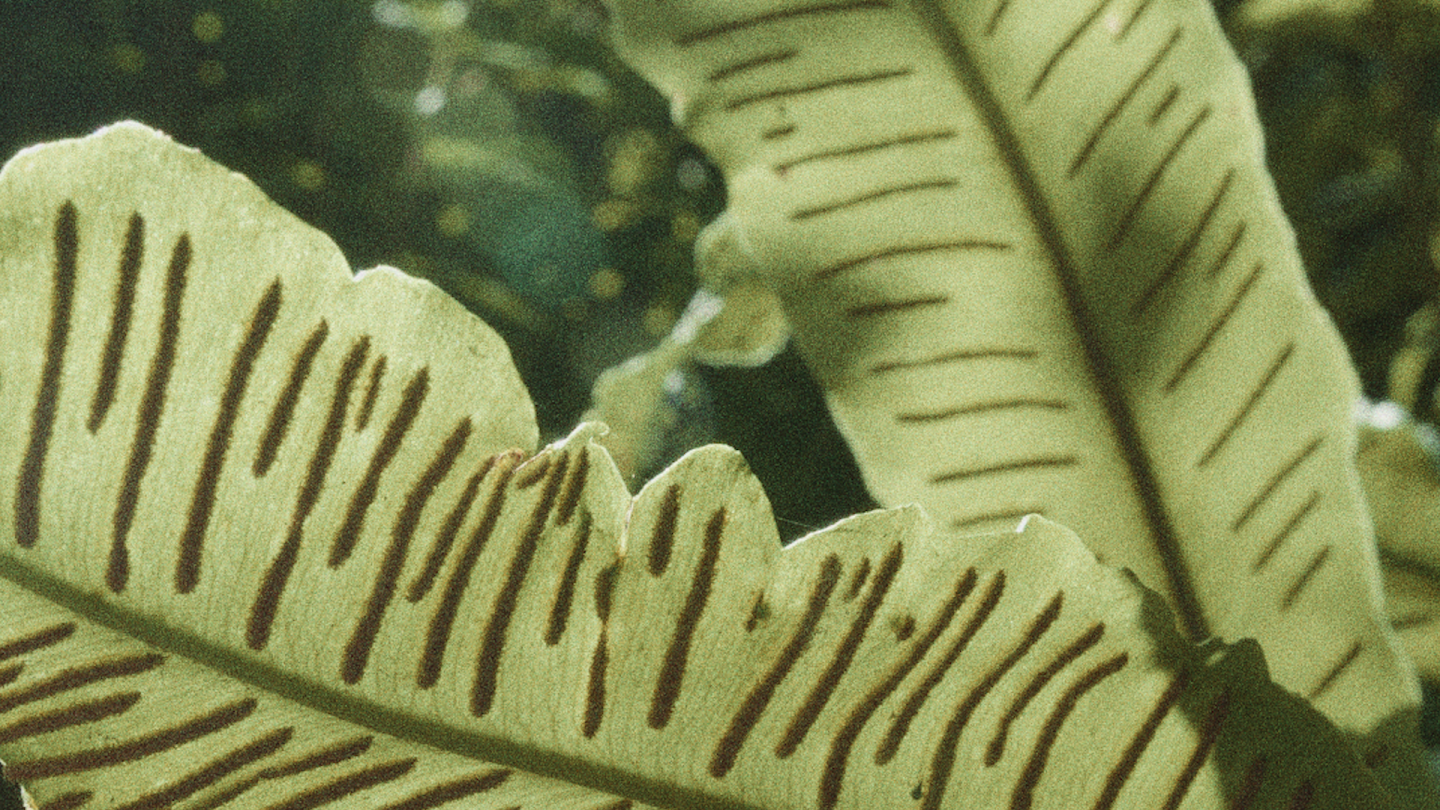

Fuelled by his daytime fascination with the natural world, the Dutch producer’s nocturnal work merges mesmerising organic – or uncannily organic-sounding – textures with driving, complex, kinetic rhythms, meticulously crafting evolving ecosystems of electronic mutation. Just a few weeks ago, Teqmun took us on an educational walk through one of our favourite spots in the world: the Amsterdam forest. Now, he sits down with Leendert Sonnevelt to dig deeper.

Words by Leendert Sonnevelt

Images by Ted Grindei & Evi Cats

I was introduced to Teqmun through Pariah’s remix of Nettle Dweller, which I enjoyed on repeat. Is that a proper introduction to who you are as an artist?

Nice. Pariah has been a big inspiration for years. In that sense, it’s representative. The fact that that remix happened was really a dream come true and it’s a fantastic track. But I also have to say: while working on new music recently, I ran into the fact that I find it difficult to make very club-oriented music. I tend to go experimental quite quickly. What I’d like to hear in a club is not always what other people want to hear. In DJ sets it works better for me, connecting really good club tracks…

What do you want to hear in the club?

I like some sense of challenge, but it shouldn’t get pretentious. A set needs rhythm but it also needs curveballs. I like it when a DJ jumps from one thing to the next; you need to stay stimulated. I find it hard to dance to a 4x4 beat the whole time. I can do it when some people are really good at it – when they keep me engaged. But I like it when something weird is happening.

Okay, and when you’re producing you go a bit more experimental. On what level? Structure? Instrumentation?

Mainly in sound design, I think. Trying to stay away from the synthesizers and instruments that are often used. If you look at the influence of machines like the Roland ones, the 909 and 808, for example… I do like using them, but then I process them with effects to the point where they’re no longer recognisable. So you hear really strange sounds. These days it’s very hard to create truly strange sounds, at least in my opinion.

Maybe it also depends on your frame of reference? When you talk to someone who doesn’t really listen to this kind of music, they might think your sounds are very strange.

True, sometimes I forget that. We’re so deep in it that things become normal very quickly. But I like it when it really triggers someone to go: “Wow, I’ve never heard a sound like this before.” That’s what I enjoy.

Let’s talk about your other profession. Online I’ve found: biologist, plant biologist, molecular biologist and scientist. What’s the correct term?

Well, at first it was “biologist,” because I did a biology bachelor – and there’s some science involved in that. I just finished my master’s in molecular plant biology. A lot of research was also molecular, which is why many people also call me a microbiologist. It all fits within the entire biology package. The master’s is called Biological Sciences and I did the molecular plant biology track. So, it’s all correct!

Where did this fascination begin?

It’s been with me my whole life. I remember as a kid in England, my parents had a small wall in front of their little garden patch, and I remember pulling that entire wall apart because there were always toads underneath. Then I kept making new little shelters for them so I could come back and see if they were still there. And that hasn’t changed at all. Still, when I’m on holiday with friends or my girlfriend, I’ll come back with snakes or lizards.

At a certain point your interest in music came into it. When was that?

That also came very early. My dad played church organ. Not because he was religious – he just loved piano and organ. My grandfather played guitar, my uncle played guitar, my mother played guitar and piano. My grandpa had an old Yamaha keyboard, that’s where I first practiced Twinkle Twinkle Little Star. At some point I discovered Eric Prydz when he released Pjanoo. I was probably 11 years old, and back then you had MTV Kids. In the video clip you saw a piano playing, but no one was playing it – you just saw the keys. During my lunch break I’d bike home to practice on my dad’s keyboard. That was the first time I got into electronic music. You could record four tracks on that keyboard, which was quite a hassle and it sounded like crap. But I tried to recreate that track, and that was the first time I tried layered production. Later, that continued with GarageBand. In high school I made tracks during classes – mostly remakes. FL Studio happened, which was a bit more advanced but still on my phone and iPad. And then I discovered Flume and Hermitude. They both used Ableton and I thought: this is amazing. That’s when my love for synthesizers started.

How long ago was that? Around 13-14 years, if you were listening to Flume?

Yes. And some seven years ago I really started discovering Ableton. I haven’t stepped away from it since. It’s such a nice program. I don’t have many synthesizers; I have a keyboard because I used to do piano and vocals. So I feel I’m quite good with Ableton and I do everything with it.

Everything in nature, every animal, has a place – a specialised place shaped through evolution and selection. And there is so much sound in nature. If you just look at birds and insects and the weird sounds they make… I think electronic music has a lot of room for that.

The link between nature and electronic music – or club music – isn’t obvious to everyone. You could say electronic music is far removed from nature, but at the same time you could argue that it gives you the space to zoom in and mimic that whole micro-level.

Yeah. I see sound in general as something super diverse, which is what you also see in nature. Everything in nature, every animal, has a place – a specialised place shaped through evolution and selection. And there is so much sound in nature. If you just look at birds and insects and the weird sounds they make… I think electronic music has a lot of room for that. Also, I heard so many sounds while working in the lab. Electronic-sounding elements: bleeps, bloops, noise in the background. And if you hear background noise constantly, your brain starts creating patterns, so you start hearing rhythms. This link – it’s hard to explain. In one of my tracks, for example, I used bee sounds, but I also made synthesizer sounds that sound a lot like bees. They come very close; when I play it to others, they can’t tell the difference. There’s also this bird, the bellbird, which makes the loudest animal sound in the world. You can’t tell me that’s not basically a flying synthesizer! So yeah – if two passions live so strongly in your head, and there’s so much room in both, the link is just there.

The way I experience your music is that it’s not always super serious. Sometimes it’s dreamy and somewhat heavy, but it also has a lightness and humour. Just the titles alone: Worms Still Have To Eat Dirt or Slug, No Escargot. Can you say something about that?

Definitely. When I made the Phototropism EP I had a pretty bad ski accident. I spent a long time in the hospital and had to do long rehabilitation. That was right at the start of Covid. Before that I had just started going to De School; I was young, the scene felt very serious. My mindset was: okay, music is interesting. The experimental stuff was very interesting, and I felt like you had to be very serious about music. The longer I’m in it now, the more I realise: how nice it is to not always be very serious about this. It’s music, it’s for everyone – enjoy it, make what you want in the moment.

For me, a track is usually a snapshot. If I don’t finish a track in a day, it usually doesn’t reach the final stage. I need an idea, finish it, then let it rest. And then I can tweak later. But I like it best when it’s a snapshot – and you can hear that in my tracks. They all have a bit of the same sound design, my sound design, but they’re still different. That often shows in the track titles too. Recently I made a track called With the Swagger of a Flattened Bear (forthcoming) – that’s about a wolverine. The concept comes from David Attenborough, because he said that a wolverine… I don’t know if you know that animal?

Let me Google…

Yeah, they can’t be tamed. They’ll fight a grizzly bear and come out alive, which I find super cool. David Attenborough described it as a kind of “flattened bear”. And I thought that title fits a track that you shouldn’t take too seriously – it has its own place, but you shouldn’t mess with it. Just like the wolverine. There’s a cute synth-bleep in it, but also a very weird synthesizer sound. And there’s a driving kick. That’s what I love. Natural situations can be so bizarre. And it is serious, but you can also look at it with a different lens… It is what it is. Sometimes funny, sometimes grim.

With the Slug, No Escargot EP I went deeper into the unruly side of nature. And with the EP in between, I was also a bit between the serious tunes and the sweeter, playful ones. Aphid Walk was inspired by an aphid. An aphid doesn’t move very quickly once it’s found a good leaf; its whole world is a branch we can just pick up. Maybe it messes with the plants in your garden. I find that a funny idea, and that becomes a track. That’s where my head is at that moment.

Crown shyness – I don’t know if you know the phenomenon – is that tree crowns prefer not to touch. There’s competition for light. Some species do this better than others, but often when you look up in a forest you see gaps between the trees. I thought: how can I mimic that in a track?

It sounds like both worlds exist next to and through each other in your mind. Can we go back to that track with the bees for a moment?

Yes. Often when I come back from a party, I make music. And before I make music, I often watch nature documentaries or read a paper – whatever I’m in the mood for. After playing at Draaimolen last year, I think I was watching Green Planet, BBC, David Attenborough. They showed that when you see bees hovering over flowers, sometimes you see them hover for a moment and leave again. I always thought that was interesting – like, can they see the flower? A bee’s vision is very different. And I wondered how they can know there’s nothing to get from a flower that looks perfectly fine. Turns out: flowers have an electromagnetic field, slightly negatively charged. And a bee has a slightly different charge. So, when a bee visits the flower and takes nectar, it changes the flower’s electromagnetic field for a while. Crazy! Bees can detect that with their sensory organ and notice: oh, someone has been here, nothing to get for me. So they don’t waste the energy to land and can move on. That’s what Flowers Are Electronic Billboards for Bees (forthcoming) is about. When I was on a campsite in France I recorded bees. At home I used those recordings to create synth sounds that resemble bees, and it became a track. It jumps from one thing to the next, it’s playful, with lots of different sections. You can hear a swarm flying over your head. Imagine: the sound of one bee is cool. A swarm – that’s so many!

Another track that has both a special concept and title is Crown Shyness. Can you elaborate on that one?

Crown shyness – I don’t know if you know the phenomenon – is that tree crowns prefer not to touch. There’s competition for light. Some species do this better than others, but often when you look up in a forest you see gaps between the trees. I thought: how can I mimic that in a track? So, I started with deep sub bass and added some white noise. Some colourful elements. And then I thought: that “shyness” reminds me of side-chaining in music production. You can side-chain with compression – people use it to make synths duck when a kick comes in. And you can use it lightly or very intensely. Anyway, that shyness sort of mirrors how all elements duck out of the way for the kick. So I thought: I’m going to make a very consistent sound – like the growth of a tree. And every now and then you hear a strong kick, representing another tree, where all elements in the track duck away very strongly.

Whoa, I’m learning a lot today. Wrapping up, what advice do you have for biology noobs? What should I pay attention to, especially in the forest?

Honestly, I mainly look at the ground. My eyes are always scanning for places where a lizard might be. Where something might be moving. But mostly… it’s training yourself to see things. To pay better attention. Another suggestion: sit somewhere, especially near water, and take the time to be still. Just look around without saying anything. You’ll suddenly start to see that everything’s in motion.

One last question. When you’re in nature, do you listen to music?

During the bike ride there or in the car, yes. But once I’m there, no. In nature you already hear so many nice sounds. Mostly I just like to unwind and hear nothing else. It’s good to feel grounded.