Amsterdam is known as a city with many nationalities. But on mainstream radio stations, the weekly charts and the annual top 2000, this diversity is rarely reflected. Many genres remain underexposed, and music from many languages is not getting the attention it deserves. But it’s bubbling beneath the surface and genres such as cumbia, traditional Iranian music and Turkish pop increasingly find their way to new audiences. In this article, we talk to four musical all-rounders and touch on their cultural background and how it influences their musical direction. They are each in their own way pivotal in the web of sending and making exciting music. The result? A bundling of four conversations about musical education, obscure cassettes, the added value of radio making and the need to document culture properly.

Words by Daan Stoop

The artists

First of all, Beraber. After producing soulful hip-hop under a different alias for a decade, the Amsterdam based producer Barış Akardere made the switch to more up-tempo territory. Besides that, he's part of Carista's exciting United Identities crew and always brings a jazzy and melodic charm to his lush house sounds. “Beraber means 'together' in Turkish” says Barış from his studio that is filled to the brim with synths. "Furthermore, I thought it was an interesting word, even if you don't know what it means." Barış used to listen to a lot of hip-hop with electronic elements, from J Dilla productions to the LA beat scene with the likes of Flying Lotus. “It was a bit later that I discovered how much I liked house music actually, when I started going out to clubs like Trouw. When I was younger I felt like there was a clear line between hip-hop and house, but when you go looking for records at places like Rush Hour, luckily these boundaries start to blur pretty quickly."

Another DJ and music collector is Coco Maria. Hailing originally from Mexico and now based in Amsterdam, she specializes in Brazilian, South-, Central American, and Caribbean wax. Her sets and radio shows are full of irresistible slices of bossa nova, samba, cumbia, and all sorts of rarities from sunnier, far-off places. From her living room - which was previously featured in this Dekmantel photo series - we talk about the Dutch rain and the musical remedies against it. “My record collection takes a big bite out of my room,” Coco Maria jokes. “Although this is not entirely mine,” she says. “I share it with my boyfriend, Palo Santo. At first we had everything mixed up, but he has completely different ordering mechanisms, so it was total chaos.” At first glance, that chaos doesn’t seem to have disappeared, but Coco Maria has an inventive system made for herself. “I classify my records by moods, not really by genre. I don't put all the Brazilian or Latin music together, but I divide them more by moods. Examples of moods are party, jazz, weird, cheesy. And there's always room for more moods. Recently I visited a friend with a collection all in alphabetical order. We talked about a record and BOOM! he took it out. I was impressed, but could never do that myself.”

Katayoun Arian (artist name: discourse) is a DJ with a curatorial practice in which she also engages with cross disciplinary work, sound, listening and music cultures more broadly. Currently, she also works at Tent in Rotterdam, a platform for contemporary art. “Music has always been an important part of my life and upbringing. At home, it especially connected me to Iranian culture, its poetry, values and beliefs that I was so grateful for later on,“ Katayoun says. “I was born in Iran, but I grew up in the Netherlands from the age of seven. Growing up with the influence of MTV and experiencing the possibilities of downloading music during the heydays of the internet, allowed me to become familiar with a wide range of music genres from a young age, from gabber in the 90's to underground hip-hop.” In 2004-2005, Katayoun dabbled in DJing at parties as a student of art history, but it was only 10 years later when she decided to take her own distinct path: “My approach to DJing is informed by the experiences I had growing up between different cultures on the one hand, but on the other hand also by what I believe is a creative and curatorial practice that can be extended to DJing”, she says.

Hala Namer, aka LazerGazer, is the youngest of the four and tunes in from her studio space at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. There she’s working on her study at the audiovisual department. “Currently I’m busy making swords and sampling weapon sounds,” she says. “I really like to go back and forth from the analog to the digital world. For another project I asked my mom, who lives in Damascus, Syria, to send me her cassette collection. She did, and I played some live sets with it here in the Netherlands recently. For Subbacultcha, I performed a live score for a film in the EYE film museum. I recorded sound code lines on cassette loops that I made. Together with some cassettes on which I damaged the magnetic tape, it created a crazy broken effect with both digital and analog elements.

"My approach to DJing is informed by the experiences I had growing up between different cultures on the one hand, but on the other hand also by what I believe is a creative and curatorial practice that can be extended to DJing” - Katayoun Arian

Influence of roots on musical direction

“I grew up with Turkish music and still listen to it a lot,” says Beraber. “That naturally shaped me, although the link to what I make and play now isn’t necessarily self-evident. Turkish music is often emotional, musically rich with a bit of sadness somewhere, and in my own productions there is also a kind of melancholy.” But when I ask Barış about his favorite Turkish songs, it turns out to be a difficult question to answer. “I find it difficult to make good recommendations out of the blue, because there are so many beautiful albums. There are songs that are released now that are incredibly beautiful and there are albums from over forty years ago that are still super powerful today,” he says.

With another project, Osdorp Tapes, Barış and Jurriaan Pots use Turkish cassette tapes for live DJ sets. “I’ve collected those tapes over the years because I used to spend all my saved money in Turkey in local music shops during summer holidays. Playing cassettes for an audience is pretty different from a normal DJ set. Beatmatching, for example, is not really possible.” With this project, they ended up in many different places, ranging from De School, FOAM and ADE to line-ups with Omar Souleyman and Altın Gün (who also play a live show at Dekmantel Connects on December 17th). "Our aim with this project was to shine some light on artists and styles in Turkish music outside the handful of names whose music found a way to European audiences already, be it folk music, Arabesque or 90's pop".

In the summer of 2019 I was working behind the bar at the Amsterdam Roots festival and I saw Coco Maria play the closing slot. Young and old people, from 8 to 80, were dancing, and cellphones were nowhere to be seen. “I remember that gig very well, I started with a Surinamese song”, Coco says with a laugh. “It caught on immediately. Then I moved on to a bit more Latin sounds. It's extremely difficult not to like Latin music. It always puts you in a good mood - it's contagious.” The rapid switch from Suriname to Colombia to Brazil is characteristic for Coco Maria. She hardly ever only plays music from one specific country in one set. "When I play, I like to show how all these genres and countries are connected, not divided."

She gathers much of her music when she returns to Mexico to visit family. What is striking there is that DJ culture is rapidly changing towards the European model. “Around 10 years ago, it was just people with CDs and a sound system. That's all you needed for a party”, says Coco. “Nowadays, the focus is increasingly on the line up and the branding of the party. That's why I sometimes go back to the past in my head, when I just played music with friends and we didn't have DJ names. In the end, we all just play music from other artists. Too much attention for the DJ steals the attention away from the music itself.”

“My mother used to record my voice on cassettes when I was younger, and now she sent all those cassettes to me,” says LazerGazer. “Besides that, they also contain music I used to practice for dancing lessons. With those cassettes, I now sometimes play live performances. Just before the second lockdown, I was the support act in Garage Noord for the band Global Charming. Equipped with cassette decks, a lot of pedals and a Tascam, I built up my set and it worked super well. I always wanted to do something like this, and when I first saw someone else playing only from cassettes, my mind was blown. The amount of times something goes wrong… haha. But the people in Garage Noord were quite receptive and nostalgic.”

“Back home, in Syria, politics really involves music and what you listen to really defines the way you think,” LazerGazer says. “What my mom sent me was really leftist music, really shady and funny with a weird political punchline. My personal collection mostly consists of trashy and popular music. I also found a cassette that my father had recorded something over, a little message about cakes. I kept it and turned it on in Garage Noord. That was funny, in the middle of the song someone suddenly presses a button and you are sucked into another world. After a few seconds it stops again, and the old track continues.”

The added value of radio

What all DJs have in common is that they used to host a show on the now closed Red Light Radio. “I certainly miss it”, says Beraber about it. “It was the perfect way for me to organize new music. I could play very broadly there and focus a bit more on records that are nice to listen to at home as well, like last year's beautiful ‘This is For You’ by Theo Parrish or the new Chaos in the CBD record on Neroli for example. Besides my shows as Beraber we also had a (semi) regular radio show with Osdorp Tapes, bringing our own cassette decks to the studio."

Red Light Radio has been closed since summer. But where some stations shut their doors, others receive more attention as a result. Club Coco, Coco Maria's weekly show on Worldwide FM, is a good example. In it she showcases her diversity. “It's a relatively new radio station created by Gilles Peterson and his team with music from all over the world. Compared to other stations their music is not so heavy”, Coco says. Club Coco is streamed from Coco’s home, but now and then she also plays at other stations. Recently, Coco went to Kiosk Radio for a duo show with the Belgian DJ Lefto. “It almost feels like a gig. At the moment there's not much to do so that radio show was something I looked forward to.”

While picking up DJing, Katayoun also found a ‘home’ at Red Light Radio in 2018. “At that point, I was listening more consistently to Iranian musical traditions from the '30s to the '80s which ultimately resulted in a self-directed mix-mode research project,” she says. “It became self-evident to collect, archive and activate the gems, musical traditions and genres that had been confined to oblivion. Two major events have pushed the rich Iranian music archive into obscurity: The Islamic Revolution of 1979, and the displacement of Iranian music production to Los Angeles, which is considered as the birthplace of a distinctive form of post-revolutionary pop music that became overbearing both in Iran as well as in the diaspora.”

“Back home, in Syria, politics really involves music and what you listen to really defines the way you think” - LazerGazer

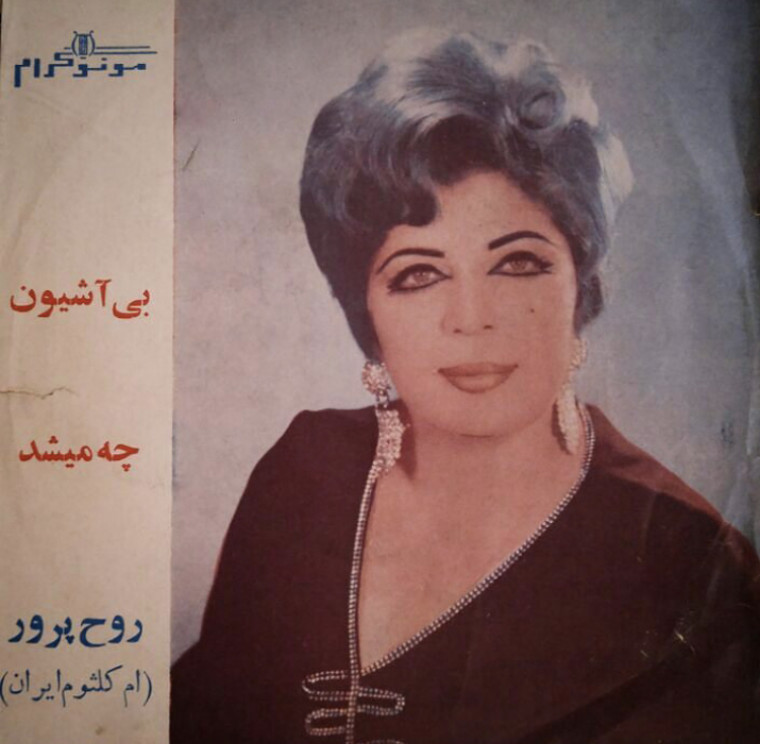

When she devoted herself to understanding and digging in this archive, she also committed herself to activate and work with it. “One of my aims was to compile a unique collection of particularly female vocalists and music from Iran dating from the early twentieth century all the way to the 1980s,” she says. "While I was discovering forgotten treasures of this wide spanning musical period, what particularly grabbed my attention was the strength of character of its female singers, some of whom have been overshadowed in the collective consciousness not only by major political events but perhaps also because of the repertoire and success of iconic performers and vocalists from the 1970s such as Googoosh.”

Sharing this heritage did not only stem from a sheer feminist and revisionist perspective. “I wanted to combine this practice with historical analysis, musicology, and from a place of understanding that culture is necessarily fluid” she says. "The latter entails that I listen with the acknowledgment that Iranian musical traditions should be understood within their own geographical disposition, and by taking into consideration cosmopolitanism, political, and cultural renewals in the modern period while adhering to decolonial perspectives." The result: a series of unique collections that gained a public feature under the moniker "discourse" at Red Light Radio. "What was amazing was that the shows also garnered attention and following in Iran,” Katayoun says. Her work can be found on her SoundCloud.

Two Iranian female vocalists, Roohparvar (r) and Parisa (l).

Document your Culture

As becomes clear from the above, thorough research and documentation of music culture is of vital importance according to Katayoun. In one of his meantime widespread and famous quotes, Carter G. Woodson, founder of Black History Month, construes it as follows: "Those who have no record of what their forebears have accomplished lose the inspiration which comes from the teaching of biography and history."

On this matter, Coco Maria points to the work of Emma Warren, a London-based journalist. Last September, she wrote a pamphlet about this theme with the appropriate title Document your Culture. In this book, she dives into Total Refreshment Center, a multi-purpose venue that had to close its doors in 2017. The place, run by visitors, was very important to the London jazz scene and the birth to a lot of bands. In articles and interviews Warren explains to them that you will only miss the place when it is no longer there. Politicians always parade with these kinds of diverse places, but when push comes to shove, they do nothing for preservation.

“In her book, Warren gives a number of tips on how to keep these kinds of places alive, through panel discussions and broadcasting radio. It’s highly recommended, especially now that through Covid-19 we find out how much we miss these kinds of places, ” says Coco Maria of Warren’s book.

Documentation and education go hand in hand, according to Beraber. “It would be nice if people here knew a little more about Turkey than döner kebab, the local garment maker and holidays in Antalya. The rich musical history and culture can be a good point to start,” he says. “Furthermore, especially in the context of 2020, it would be good that we pay more attention to education about the 'guest workers' who came here in the '60s and '70s, why it is that so many Turks came to live in the Netherlands and under what conditions all of this took place. The history of our own communities basically. There's lots of interesting music made by Turks living in Europe, Germany especially, that touches on these topics. Derdiyoklar Ikilisi for example, who have really great music and insane live shows, while being outspoken and critical on topics like housing, working conditions and the racism that these people had to face when they arrived in their new countries.”

LazerGazer recommends I try out music by Amr Diab and Roubi. “A lot of people reject this kind of music to be part of the culture, but for me it was essential in discovering my queerness,” she explains. “Later on I realized that this kind of music was one of the few references we had to something that is not the typical and a bit more extravagant.”

Photos by Tim Buiting & Dennis de Groot